Continued From Alesia, Gallia Lugdunensis Part I

Adjacent to the northern portico of the forum is one of the most interesting elements of Alesia, the so-called Monument of Ucuetis. This structure was built into the hillside, and so much of it is at a lower area than the forum. It seems to have been a sort of guildhall and meeting place for the bronze workers and blacksmiths of the town. It also seems to have had a religious function and was dedicated to the Celtic deity Ucuetis and his consort Bergusia. Ucuetis appears to be a patron deity to craftsmen while Bergusia seems to be associated with prosperity. The building itself is mostly accessible. There is a large courtyard area surrounded by square columns, some of which are preserved. That area is located below the level of the forum. On the south side of the courtyard are some additional structures, now covered by a modern protective roof, that were the lowest level of a three story building. This level mostly exists in an area that was carved out of the hillside.

Back to the south, south of the southern portico of the forum, is an elevated platform on which to view the site. It’s a modern construction and doesn’t correspond to anything in the ancient settlement. Adjacent to the eastern foot of the platform/mound are some remains of a road and some scant vestiges of the adjacent structures, which are not identified, along the roads. The remains of a Christian basilica dated to St. Regina are apparently covered to the west/southwest, and a few stones marking the area are all that is visible.

The final excavated area of ancient Alesia is made of a residential and artisan area in the eastern part of the site. This area is bisected by a decumanus running through the middle, and further divided by an unexcavated area dividing it into an eastern and western portion. In the western part, the most interesting aspect is the house on the south side of the street has a cellar with niches for amphorae storage. The pads on which the amphorae were placed are re-used mill stones. There is another cellar toward the center of the house, but access to the house is roped off, so the central cellar isn’t really visible in any meaningful way.

The eastern part of the residential area is a little more extensive. Most of the buildings here have cellars, some seemingly with more than one. Most of it is hard to discern any clear form; these are not the typical Mediterranean atrium-style houses that have a fairly easily identifiable layout. A number of wells can be seen throughout as well. There are a few points of particular interest here. The first being that the street that runs through the middle of this district would have been lined by a small portico. This is somewhat apparent by a few remaining column fragment set up along it. In the northwestern portion of the neighborhood is a covered area that protects a series of metalworking furnaces that have been discovered; a testament to the metalworking trade in Alesia.

In the southeast part of the district is another covered area that protects some remains of a hypocaust system. Some other vestiges of the hypocaust system are also visible in the uncovered area around it, particularly to the west. There was a completely covered and enclosed area just to the west, in the area of what appears to be one of the cellars (judging for satellite images and plans), where perhaps ongoing work is being done. The southern part of the neighborhood here is also bounded by a small street. Nothing in the residential area is directly accessible, as it is all roped off keeping the visitor around the outside or down part of the street through the middle, but not all the way through. There are a few guided paths in to see the metalwork furnaces.

In total, it took me about an hour to walk through the archaeological remains of Alesia. Many things are largely roped off, keeping visitors at the exterior, which kind of limits the detailed viewing of a lot of things. There are signs at most points of interest with brief explanations in English, French, and German. A few also have reconstructions or plans that make visualization helpful. Though not ancient, it is worth noting that about 600 meters west of the site (and also accessible by car) is a statue of Vercingetorix erected by Napoleon III in 1865.

The MuséoParc Alésia is located about 2.5 kilometers away (about a 5 minute drive) on the south side of Venarey-les-Laumes at 1 Route des Trois Ormeaux. There is a large adjacent car park. It has the same seasonal opening hours as the archaeological park; daily from Feburary 15th to March 31st and in November from 10:00 to 17:00, In April, May, June, September, and October from 10:00 to 18:00, and in July and August from 10:00 to 19:00. It is also closed the rest of the year (December through mid-February). Admission is 9 Euros, or 12 Euros in combination with the archaeological park.

The relatively new museum is definitely geared as more of an interpretive center. While there are a number of actual archaeological artifacts, and a few of them are quite nice or historically significant, the emphasis really does seem to be on creating a multimedia experience relating the history of the site, and in particular, the battle of 52 BCE. There are lots of reconstructions of weapons and armor that would have been used and diagrams of the battle and the famous siege works. But, there are also some actual artifacts in the form of weapons and armor recovered that were actually vestiges of the battle. As well, there are also some general objects found in the excavation of the city.

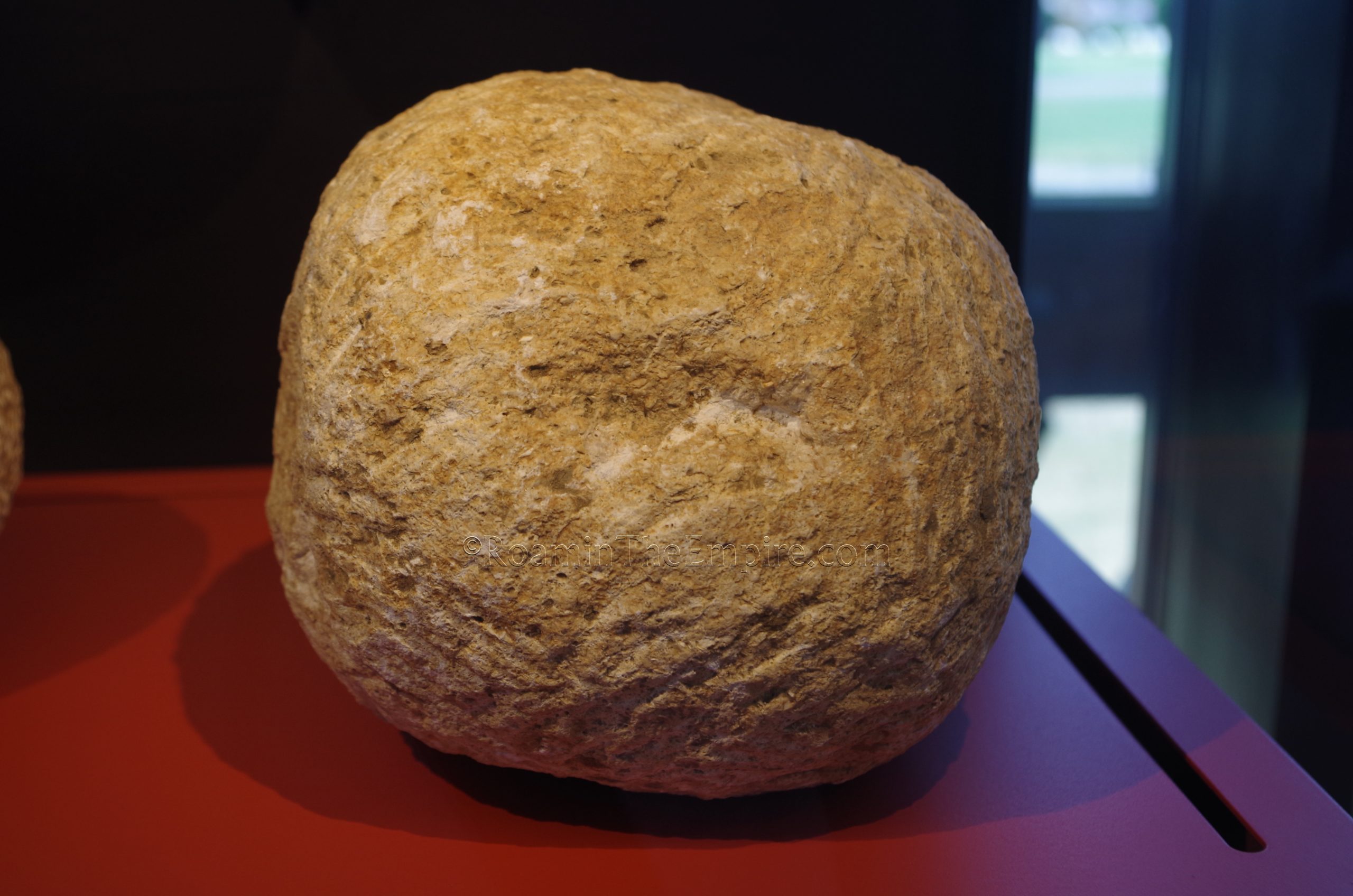

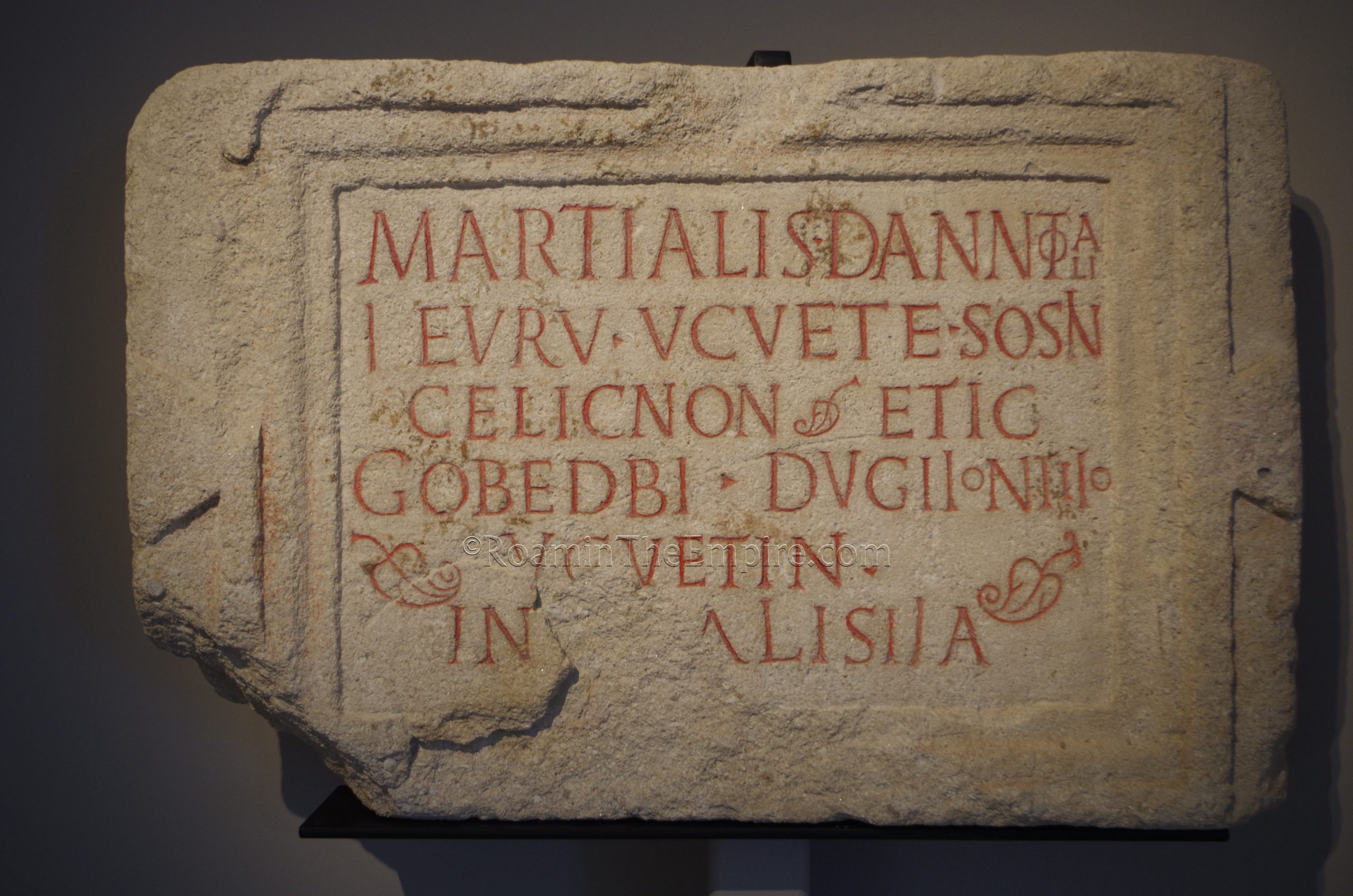

Some of the highlights of the museum include, again, some of the artifacts related to the Battle of Alesia. Some stone onager missiles, stimuli (caltrop-type barbs) that were noted by Caesar as being part of the defenses, as well as various other arms and armor, including a few pieces that were apparently recovered during Napoleon III’s excavations in the area. I found some of the objects related to the local religious life particularly interesting as well, including a dedication to Apollo Moritasgus (an epithet of Apollo and his merging with a local healing god, who was worshipped at a nearby healing spring) and his consort Damona and an inscription dedicated to Ucuetis from the eponymous building in the city. There is also a Gallic inscription transcribed in the Greek alphabet a well as statues of Epona and the Mater of Alesia. A few objects from later periods are also on display. Most of the information in the museum is presented in English, French, and German.

The top floor of the museum has an outdoor viewing area that extends all the way around the museum with panels pointing out landmarks related to the battle that can be seen. Outside the museum, and accessible only through the museum, is a reconstruction of about a 100 meter portion of the circumvallation and contravallation walls, complete with the additional defensive measures that ran with the walls. This reconstruction is close to the original course of the original lines of the fortifications. A fair amount of the circuit of these walls been identified. Unfortunately, there doesn’t seem to be anything visible remaining of these siege works today. I took a look at a few more easily accessible areas at which the course of the works are identified as having run, but didn’t really see anything visible.

I spent about an hour and a half in the museum and at the reconstruction of the lines. Someone less familiar with the battle and the Gallic Wars could probably spend a bit more time, though. I tended to skip over some of the stuff I was more familiar with. In all, it was about 3 to 3.5 hours to see the museum, statue, and archaeological park including travel time (via personal vehicle) between the stops. The historical significance of the battle makes it an interesting stop, and the museum does a great job of contextualizing that.

An interesting nearby and related stop is the hilltop town opposite Mont Auxois to the southeast; Flavigny-sur-Ozerain. This hill was apparently the site of one of three military camps struck by Caesar during the siege as the lines of defense made use of the hill and partially encompassed it within the perimeter. It is also the camp that supposedly hosted the field hospital. Today, Flavigny-sur-Ozerain is famous as the production site for the popular Les Anis de Flavigny candies that have apparently been produced by Benedictine monks in the abbey since the 16th century CE. The use of anise here, according to tradition, dates back to medicinal use of anise at the Roman field hospital and subsequent use at the abbey in successive periods. The name of the town is also said to have been derived from the name of one Flavinius, a veteran to whom Caesar awarded land after the victory here. The spot was referred to as Flaviniacum at the founding of the abbey in the 8th century CE.

Not much remains from the Roman occupation of this hilltop. Some remains of the Carolingian crypt and some of the earliest phases of the abbey church dating to the 9th through 13th centuries CE are open and able to be freely visited. Within the crypt, though, one of the column capitals is a re-used Gallo-Roman block carved with the relief of a head on it. Apparently some of the other materials in the earliest phases of the church are also likely re-used, but, there isn’t much of the way of being able to differentiate it. Unfortunately this about does it for the vestiges of the Roman and Gallo-Roman occupation. It is a worthwhile stop for anyone that enjoys anise, as the entire town smells like it due to the candy production. The visitor’s center for Les Anis de Flavigny is literally steps away from the abbey excavations, and in addition to a little interpretive center, there’s a gift shop with opportunity to sample the many varieties of the candy. It is worth a quick stop if you’re in the area of Alesia. There’s a large free parking lot on the south side of town.

Sources:

Caesar, Julius. Commentarii de Bello Gallico, 7.34-90.

Diodorus Siculus. Bibliotheca Historica, 4.19, 5.24.

Grant, Michael. A Guide to the Ancient World: A Dictionary of Classical Place Names. New York: Barnes & Noble Books, 1997.

Pliny the Elder. Historiae Naturalis, 34.48.

Plutarch. The Life of Caesar, 27.1-8.

Smith, William. Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography. Walton & Murray, 1870.

Stillwell, Richard, William L. MacDonald, and Marian Holland. McAllister. The Princeton Encyclopedia of Classical Sites. Princeton, NJ: Princeton U Press, 1976.

Strabo. Geographika, 4.2.3.