Most Recent Visit: June 2016.

Today the site of the third largest city in Spain, after Madrid and Barcelona, Valencia’s origins go back over 2000 years to 138 BCE, where, after a protracted war with Iberian forces led by the Lusitanian commander Viriathus, the consul Decimus Junius Brutus Galaico founded the colony of Valentia Edetanorum for veterans of that conflict. Which side of the conflict those veterans fought on, though, seems to be a matter of debate. The most common translation of Livy’s account of the foundation of Valentia is worded in a way that would indicate that those settled at Valentia were troops who had fought under the orders of Viriathus, the enemy combatants. An alternative translation states, rather, that they were troops who had fought at the time of Viriathus, instead raising the possibility that they were Roman veterans. The archaeological evidence would suggest that it is the latter that is true, as tablets found at Valentia do not bear any names associated with the local tribes, which would be expected if the initial colony was composed of the indigenous troops.

Whatever the composition of the settlers, there does not appear to have been a pre-existing settlement at the site. Though Avienus states in the Ora Maritima that there was the previous settlement of Tyris at the location, there does not seem to be any other evidence to suggest this is the case. The town’s name, Valentia Edetanorum, seems to first be a derivation from the Latin word for ‘valor’, probably in reference to the veterans settling there. The Edetanorum is a reference to the area, populated by the Edetani people.

During the Sertorian War, which ran from 80-72 BCE, Valentia pledged support to Quintus Sertorius. In 75 BCE, after a victory in the vicinity of Valentia, forces under the command of Pompey destroyed the city as punishment for siding with Sertorius. The previously mentioned tablets mention a second set of veteran colonists being settled at Valentia, and it is likely that this second settlement occurred shortly after the city’s destruction in 75 BCE. One of these tablets is dedicated to Lucius Afranius, one of Pompey’s lieutenants, suggesting he was likely responsible for the settlement. This also coincided with a rebuilding of the city. While it doesn’t feature any further in the historical record after this, aside from a brief mentions by Pliny the Elder and Pomponius Mela, the city seems to have flourished by the 1st century AD, perhaps owing to a prominent position along the Via Augusta.

Getting There: Being the third largest city in country, Valencia is well connected to the other major cities in Spain via bus and rail. There is also an airport located on the outskirts of the city that is connected to the center via a metro line.

Despite the prominence of Valentia during the Roman period, though perhaps due to its continued importance through the centuries, very little of the Roman remains are exposed. In fact, there is really only one good example of in-situ archaeological remains from the Roman period, the Centre Arqueològic de l’Almoina, just to the northwest of the cathedral. The site sits on and below the Plaza Décimo Junio Bruto, named after the founder of the city. A large window in the plaza allows natural light into the site below, but also offers somewhat of a view down into the excavations. As one might expect, though, it’s not very clean and doesn’t seem to offer very good views.

I had visited Valencia before, in late 2008 and early 2010, not long after the museum opened in 2007. Both times, however, were during the winter, and at the time the site was only allowing guided tours of the remains. Unfortunately, the times of the guided tours were few and far between during the winter, and I never got a chance to see it. These days, though, a guided tour is not needed and the site can be visited freely. The site is open from 10:00-1900 Tuesday through Saturday, 10:00-14:00 on Sundays and holidays, and is closed on Mondays. Entrance is 2 Euros, but is free on Sundays and holidays. A combination ticket for visiting other sites and museums in Valencia for 3 days can also be purchased for 6 Euros.

On the entrance level of the site, there is a small museum with some miscellaneous finds from the excavations, as well as a significant portion devoted to glass objects. In addition to the Roman remains, there are also some remains from the Visigothic and Islamic periods of occupation as well. For instance, the large nymphaeum at the entrance to the archaeological area is overlaid by the remains of the 11th century CE Islamic alcazar. The remains of a few Visigothic tombs and religious structures, located primarily in the western portion of the site, are also scattered around the site. The core of the remains are remains dating from throughout the life of the Roman city.

There is a circuit of catwalk paths that take visitors around the various areas of the site. The large central area of the site is taken up by a portion of a 2nd century BCE bathing complex, perhaps dating from around the foundation of the city, that includes the remains of the apodyterium, caldarium, and tepidarium. Heading clockwise, the next remains encountered are a series of Visigothic constructions and then a portion of a 3rd century CE Roman food production space that would have faced on the cardo maximus of the city.

Adjacent to that is an aedes augusti from the 1st century CE that was part of the basilica, a small corner of which is preserved. Along the path a little further is the curia, also constructed in the 1st century CE. Along the northern wall of the site are the column pads, and a few reconstructed columns that would have formed the colonnade along the western edge of the forum. The colonnade, dated to the 1st century CE, would have enclosed an estimated 6,900 square meters of forum area. Throughout this area are various fragments of architectural elements as well as a number of inscriptions

Along the northern edge of the site area a series of horrea and tabernae dating to about 100 BCE. Running along the excavated street in front of the shops is the remains of a drainage channel. This meets with a portion of the decumanus maximus that runs along nearly the entire length of the site. Also near this intersection is a small exposed portion of a structure made of mud brick, dating to the foundation of the city in 138 BCE.

In the far northeastern corner of the site is a display dedicated to the necropolis of the city, though not associated with that particular sport in the actual Roman city, as it would have been well within the walls. Another view of the 1st century CE nymphaeum is available from this spot, as well as a 2nd century BCE pool that was associated with cult practices related to water divinities.

At the time I visited, the site and museum were less than 10 years old, and it really showed. The layout and displays are quite modern, as is the presentation of information. Signage is frequent and is in Spanish, Catalan, and English. Most buildings had bronze (or some sort of metal) models at their information boards to show what remains of the building, as well as what the larger building would have looked like in the current state of preservation. This was particularly helpful when there were multiple levels of occupation intersecting at some points. It’s really difficult to find anything failing at the site, as the presentation was quite well done on nearly all levels.

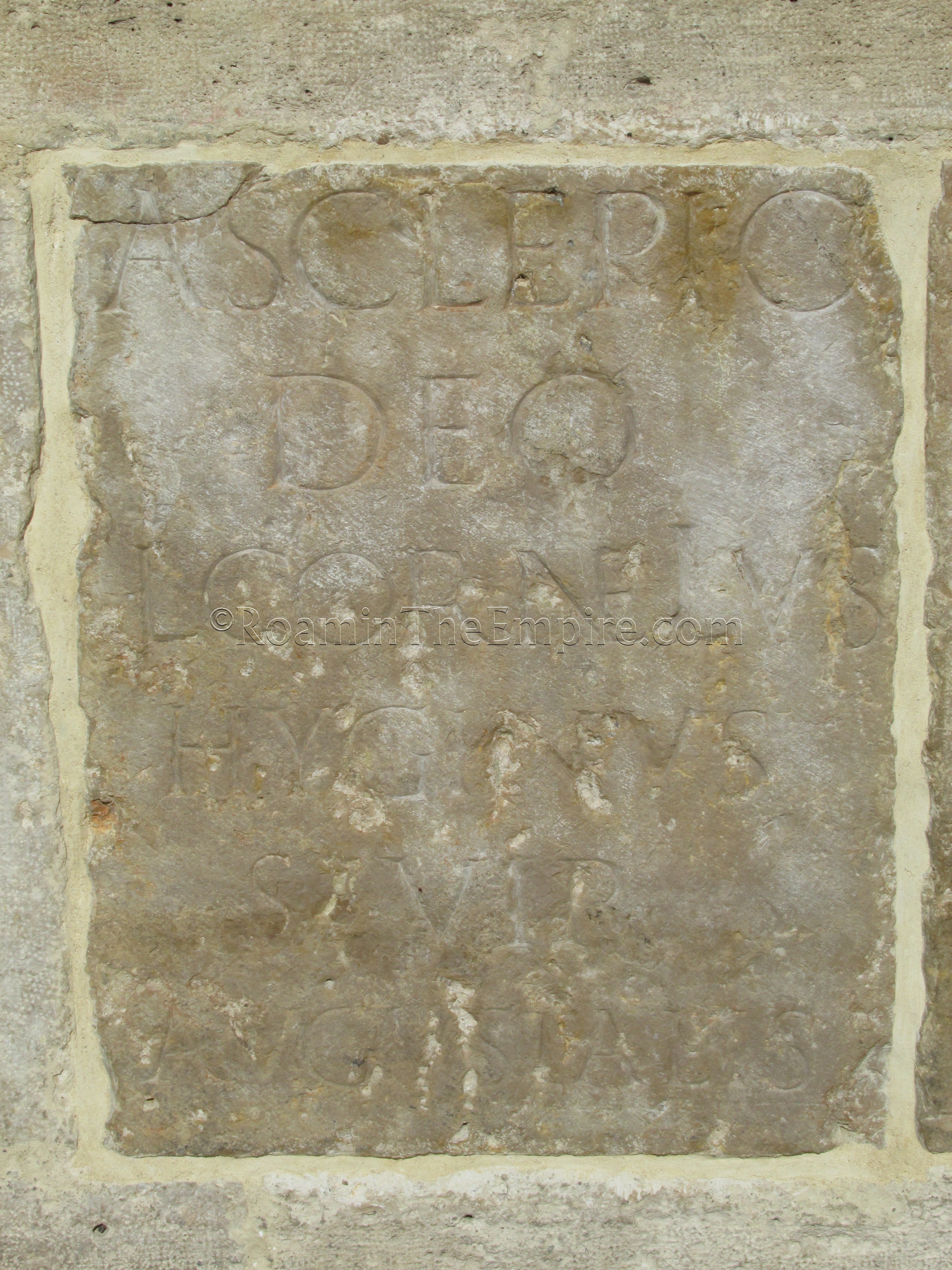

To the west, on the other side of the Basílica de la Mare de Déu dels Desemparats, the Plaza de la Virgen is thought to have been the location of the forum of the city. On the west side of the Basílica de la Mare de Déu dels Desemparats, facing the Plaza de la Virgen, are some Latin inscriptions incorporated into the construction of the building.

In the nearby cathedral, the Iglesia Catedral-Basílica Metropolitana de la Asunción de Nuestra Señora de Valencia, which is essentially to the southeast of Plaza de la Virgen, and very difficult to miss, there is an archaeological crypt. The crypt is open Tuesday to Saturday from 9:30 to 14:00 and again from 17:30 to 20:00 and on Sundays and holidays from 9:30 to 14:00, with no evening hours. It is closed on Mondays. The entrance to price is 2 Euros normally, but free on Saturdays, Sundays, and holidays. This site is also part of the 6 Euro, 3 day combination ticket mentioned previously.

The remains in the archaeological crypt are primarily Visigothic period or later, but there are a few small fragments from a 1st-2nd century CE Roman house. The remains aren’t particularly well labeled and it’s a little difficult to make out exactly what’s being indicated on the placards throughout; it’s a rather haphazard display, but I have to give them credit for making it available to view at all. One particularly interesting point near the beginning is what is labeled as an ‘iron fence’ from the Roman period, but actually looks more like an iron window grate, now embedded in the ground. Other than that, it is mostly just fragments of wall here and there among later remains, without any larger structure clearly visible from what exists now. It only takes about 15 minutes to get through, and the price is right at 2 Euros or free depending on when visited, so it’s hard not to recommend visiting based on that.

Most of the archaeological remains recovered from Valentia and the surrounding area are housed at the Museu de Prehistòria de València, located in a building with a few other museums at Carrer de la Corona 36, in the northwest part of the historic center of Valencia. Despite the name, the museum has a fairly sizable collection that includes a section on the Roman life of the city, and there is no specific archaeological museum in Valencia. The museum is open Tuesday through Sunday from 10:00 to 20:00 and is closed on Mondays. Admission to the museum is 2 Euros, except on Saturdays, Sundays, and holidays, when it is free.

The Roman collection is pretty standard; it’s primarily composed of the typical spread of ceramics, small household items and funerary inscriptions. In addition to those finds are a mosaic and a fairly nice numismatic collection of coins from throughout Spain. The highlight of the collection, though, is probably the Apollo of Pinedo. Found in the waters of Pinedo Beach, the reclining bronze statue of Apollo is an imperial copy of a Hellenistic statue from the 2nd century BCE. The statue of Bacchus displayed in the Roman collection is, unfortunately, a copy of a statue currently housed in the Museo Arqueológico Nacional in Madrid.

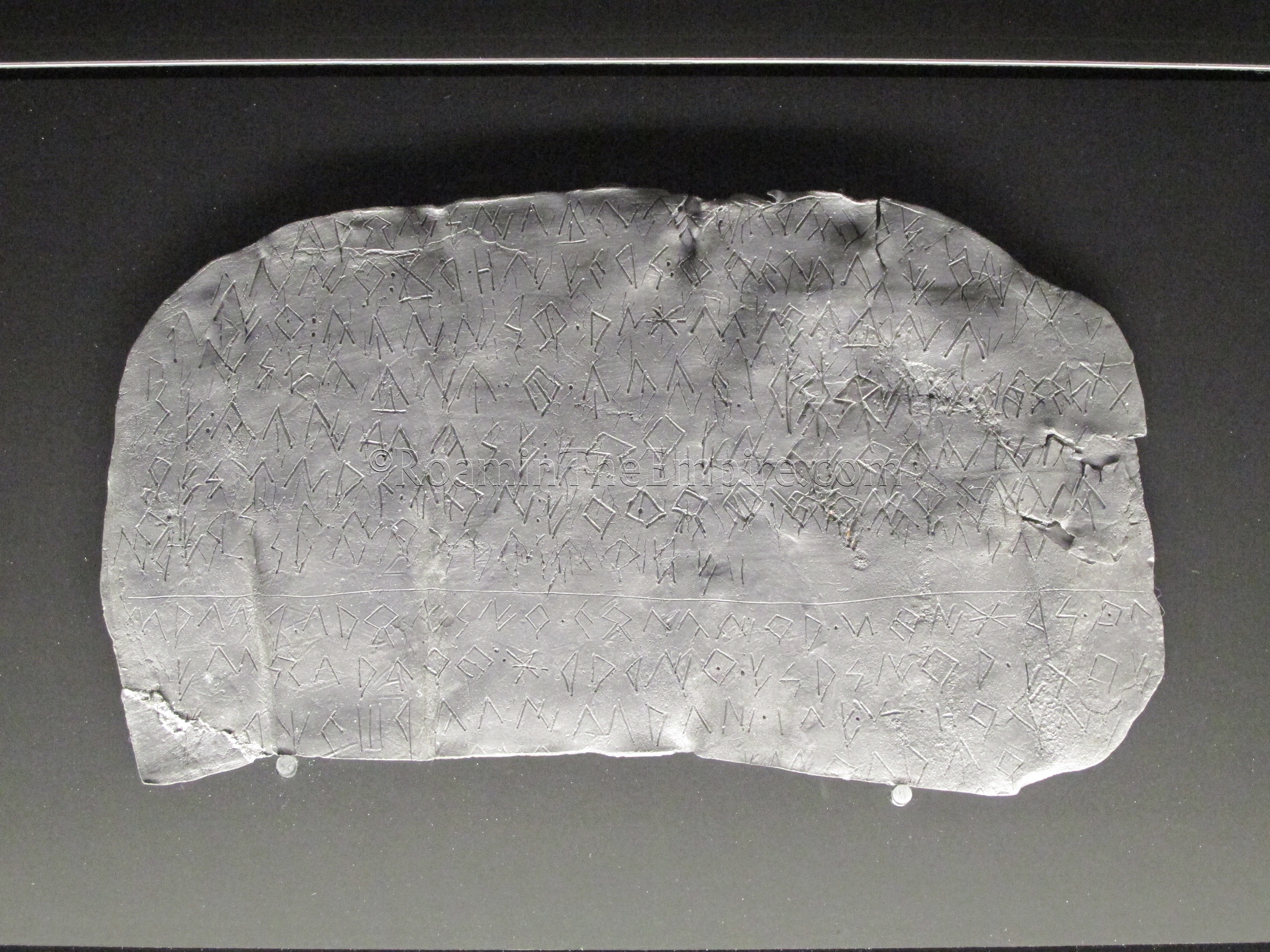

In addition to the Roman collection is a fairly decent pre-Roman Iberian collection. Of particular interest here are a series of Iberian script inscriptions on lead tablets, stone, and ceramics. The Iberian collection is rounded out by a large collection of ceramics and smaller objects such as votive bronzes and numismatics. As the name of the museum would suggest, there is also a collection of prehistoric objects as well.

It took me about two and a half hours to get through the entirety of the museum. I paid particular attention to the Roman and Iberian collections, but didn’t take as detailed a look at the prehistoric section, as is pretty common with me. There wasn’t very much English on display, as most things were signed in Spanish and Catalan, or possibly the Valencian dialect of Catalan. By and large, though, given one understands the languages, there seemed to be a fair amount of information provided. The lighting was quite bad in some areas, though surprisingly not at the numismatics displays, which seems to be the norm in a lot of museums, I’ve found. Overall, it’s a pretty good museum with a few very nice pieces and a good selection of more common artifacts.

Sources:

Curchin, Leonard A. Roman Spain: Conquest and Assimilation. New York: Routledge, 1991.

MacKendrick, Paul. The Iberian Stones Speak: Archaeology in Spain and Portugal. New York: Funk & Wagnalls, 1969.

Pliny, Naturalis Historia, 3.4.3.

Plutarch, The Life of Pompey, 18.

Pomponius Mela, Description of the World, 2.92.

Stillwell, Richard, William L. MacDonald, and Marian Holland. McAllister. The Princeton Encyclopedia of Classical Sites. Princeton, NJ: Princeton U Press, 1976.