Most Recent Visit: June 2016.

Up the coast from Valencia about 30 kilometers is the town of Sagunto. From the middle ages until the 19th century, the town was known Morviedro, derived from the Latin muri veteres, a nod to the ample ancient remains here. In the 19th century, however, the name was changed to Sagunto to reflect its ancient Roman name of Saguntum.

Saguntum seems to originally been founded in the 5th century BCE as the Iberian city of Arse on the promontory that overlooks the city, where today the castle stands. Though generally in the territory of the Edatani peoples, it doesn’t necessarily seem to be the Edatani that settled this particular town. Livy, probably incorrectly, states that the inhabitants of Arse were of Rutulian and Zakynthian origin. This was probably an attempt to justify Rome’s close relations with the city, as were Pliny and Strabo’s assertions of Zakynthian rather than Iberian origin of the townspeople. Prior to the start of the Second Punic War, the people of Saguntum started to enjoy close relations with the Romans, despite being well south of the Iberus (Ebro River) which was laid out as the demarcation line of Roman and Carthaginian spheres of influence according to a treaty of 226 BCE. This seems to, at some point prior to the Carthaginian attack on the city, become a protectorate relationship, exacerbating Carthaginian feelings that the relationship between Saguntum and Rome constituted a violation of the treaty. There are suggestions, however, that the Roman relationship with Saguntum pre-dated the Ebro Treaty, perhaps as early as the Roman diplomatic mission to Hispania in 231 BCE to investigate the Carthaginian expansion there under Hamlicar Barca. If this were the case, and a Roman aligned Saguntum was status quo at the time of the Ebro Treaty, then it’s possible that rather than attempting to check expansion of Roman influence, the attack on Saguntum was either a direct attempt to draw Rome into war, or was legitimately the result of a local conflict between Saguntum and its Carthaginian-aligned neighbors, as the Carthaginians supposedly claim according to Polybius.

In 219 BCE, the Carthaginians, under Hannibal, besieged Saguntum. While Rome protested the move, and may have even had advance warning that the attack was coming, they ultimately sent no assistance to the city. Livy mentions that there may have been some degree of regret amongst the Romans in not coming to the aid of Saguntum, particularly while Hannibal was running amok in Italy besieging their own cities. A fictionalized account of the siege is recounted in the 1st century CE Punica by Silius Italicus. The siege itself lasted eight months and apparently came with heavy casualties for the Carthaginians before they were finally able to break through the defenses of the Saguntines. Livy states that Hannibal gave the citizens of Saguntum the option of leaving unarmed and with only two garments after the Carthaginian victory was assured. The Saguntines apparently refused, and began destroying the spoils that were to go to the Carthaginians in a fire and throwing themselves upon it. Those adults remaining were killed for these acts when the Carthaginians entered the city.

Taking this Roman-aligned city so far south into the Carthaginian sphere of influence allowed Hannibal to continue on with his march into Italy without having to worry so greatly about a Roman landing of troops in this area. Saguntum remained under Carthaginian control until 212 BCE, when it was liberated and rebuilt by Publius Cornelius Scipio and Gnaeus Cornelius Scipio Calvus. During the Sertorian Wars, The area around Saguntum was traditionally thought to be a possible location for the campaign deciding battle between Sertorius and Pompey, but, modern scholarship has cast some doubt on that. During the Augustan period, the city gained municipium civium Romanorum and was well-known for pottery production.

Getting There: It is easiest to get to Sagunto from Valencia. From Valencia Nord, the main train station, the C-5 or C-6 lines of the Valencia Cercanías both follow the same route until Sagunto (or Sagunt as it is referred to on the Valencia Cercanías website) before branching off. The C-6 line runs more often, but between the two there are typically at least two departures an hour from 6:00 to 22:00. The trip takes between 32 and 37 minutes, with the estimated times sometimes differing for the same lines. A zone 4 ticket is needed, which cost 3.70 Euros when I went. The train returns to Valencia with about the same frequency, though trips sometimes take up to 47 minutes. Check the Valencia Cercanías website for updated information and the exact schedule. Once in Sagunto, everything is within walking distance.

There are a number of things to see in Sagunto, though only a few of them really have admission, and among those, as is typical with smaller Spanish towns, the hours of operation can be very strange and limited. Since there are quite a few sites, I’m just including a map with the site positions marked, rather than giving detailed descriptions of a route. The infrequent opening hours of some of the sites also makes a standard route a little difficult. I had to go back and forth between areas a few times because of this. I will try and work my way in a semi-logical fashion down from the promontory overlooking the modern city, though, as that was generally what my route consisted of.

Overlooking the town is the Castillo de Sagunto, a set of fortifications dating to various periods, primarily starting in the 15th century CE. This promontory was also the location of the original Iberian settlement of Arse, and after the Carthaginian destruction of the city, also became the location of some of the more important Roman constructions. The castle is open during the summer (June 1st to October 1st) from 10:00 to 20:00 on Tuesday through Saturday, and from 10:00 to 14:00 on Sundays and public holidays. The rest of the year it is open from 10:00 to 18:00 between Tuesday and Saturday, and 10:00 to 14:00 on Sundays and public holidays. It is closed on Monday year round. Admission is free.

While there may be some scant Roman remains to be found throughout the castle grounds (small fragments of pavement and smaller, possibly reused and refurbished cisterns), the main bulk of the Roman remains are centered in the eastern part of the castle. Coming out of the entrance area and heading up to the main level of the castle, is the Plaza de San Fernando. Right across from the entrance through the fortification walls of the castle are the foundations of some buildings, which were at the time I visited, quite overgrown by brush, but still discernable. These are apparently the foundations of some Roman era buildings, possibly a portico. While there is no on-site information, and my research has revealed little else on the subject, the construction of these walls does seem to be relative consistent with some of the other constructions in the more securely identified Roman sections of the castle.

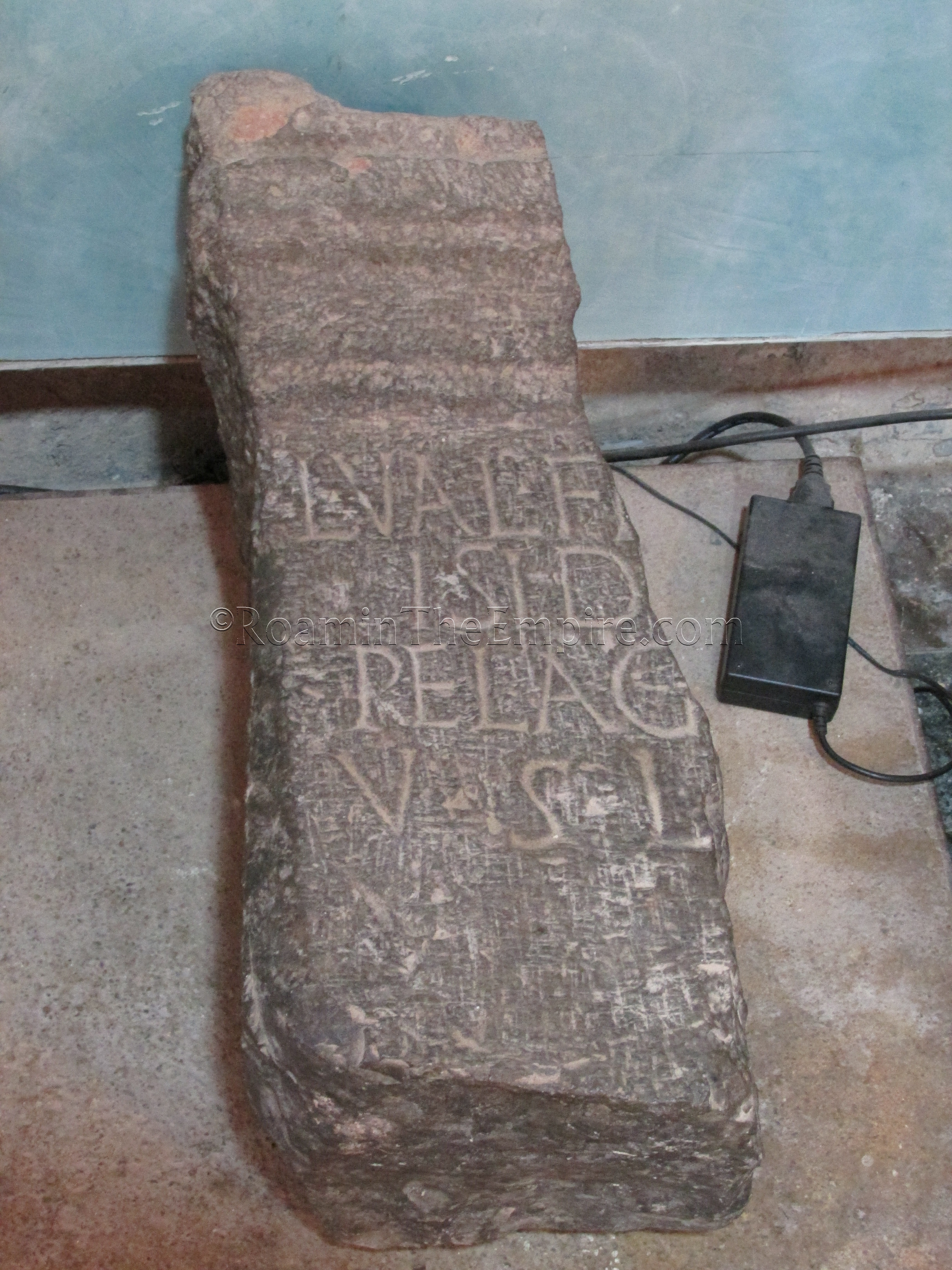

Just beyond the building foundations is a modern building which houses the lapidarium for the site. The finds in the lapidarium mostly consist of funerary inscriptions and some honorary inscriptions. There a few architectural fragments as well. Of particular interest was a fragment of an inscription noting the restoration of Saguntum by Publius Cornelius Scipio after it was recaptured by the Carthaginians.

Continuing to the east is the Plaza de Armas, which is the location of the forum of the original, Republican era settlement. Most of the remains in this area are from the Augustan period, though the temple on the north side of the forum seems to have its origins in the Republican period. The open area of the forum is presently a little difficult to clearly discern, visually, because there are some later structures built in that area and presently excavated. Entering the plaza, the robust walls excavated on the west side belong to the basilica that stretched along much of the western side of the forum. Some scant remains of the western portico are also visible.

On the south side of the forum is the remains of a very large cistern that is built into the southern slope of the hill. Some drainage channels can be seen in the area which run towards the cistern as well. Along the eastern edge of the forum are the remains of some tabernae. The northeast corner of the forum houses what is identified as the curia, though there is still some speculation on that. The remains of a large, architectural inscription are also located and displayed in this area. On the north side is the Republican era temple. Much of what remains of the temple is actually at a lower level than the forum, and so to see those, the stairs down on to the north side of the hill need to be taken. There are a couple signs present that explain the remains in this part of the castle.

Continuing out of the Plaza de Armas, east to the Plaza de Almenara, there isn’t much left. There are a few cisterns in the central part of the Plaza de Almenara that are dated, at least originally, to the Roman period. Though I did not have time to do any exploring, there are also apparently the remains of both Roman and Iberian constructions on the southern and eastern slopes of the hill, including part of the original Iberian fortifications.

Outside the walls of the castle on the north, along the road back down to the city, built into the side of the hill are the remains of the Roman theater. The theater has essentially the same hours as the castle, though the change in times is a little different. It is open during the summer (April 1st to October 31st) from 10:00 to 20:00 on Tuesday through Saturday, and from 10:00 to 14:00 on Sundays and public holidays. The rest of the year it is open from 10:00 to 18:00 between Tuesday and Saturday, and 10:00 to 14:00 on Sundays and public holidays. It is closed on Monday year round. Admission is free.

Built during the reign of Tiberius, the theater holds about 8,000 spectators. Unfortunately, the theater is very heavily restored. Only some very small fragments of the scenae area remain, most of it is rebuilt in modern materials. The theater apparently served as a materials quarry in the middle ages, so much of the theater was robbed of construction materials. Some areas of the cavea are and in decent shape, while other parts are in a poorer state of preservation. Much of the central area of the cavea has a concrete shell constructed over it so that there is stable seating for modern performances at the theater. Looking at the edges of this area, it seems as though the concrete overlays the original seating, rather than replaces it outright, which is somewhat of a relief. The passageways within the cavea look to be a mix of original and restored portions. There isn’t much in the way of interpretive information for the theater. I didn’t see any signs or placards explaining anything, but, for free, it’s certainly worth the stop.

Heading further down into the city is the Museo Histórico de Sagunto (Museu Històric de Sagunt), which houses the archaeological collection recovered from excavations in the city. The museum is located at Carrer del Castell 23. The museum is also sometimes referred to as an archaeological museum, as the collection is primarily archaeological materials. It is open during the summer (June 1st to September 30th) from 10:00 to 20:00 on Tuesday through Saturday, and from 10:00 to 14:00 on Sundays and public holidays. The rest of the year it is open from 10:00 to 18:00 between Tuesday and Saturday, and 10:00 to 14:00 on Sundays and public holidays. It is closed on Monday year round. Admission is free.

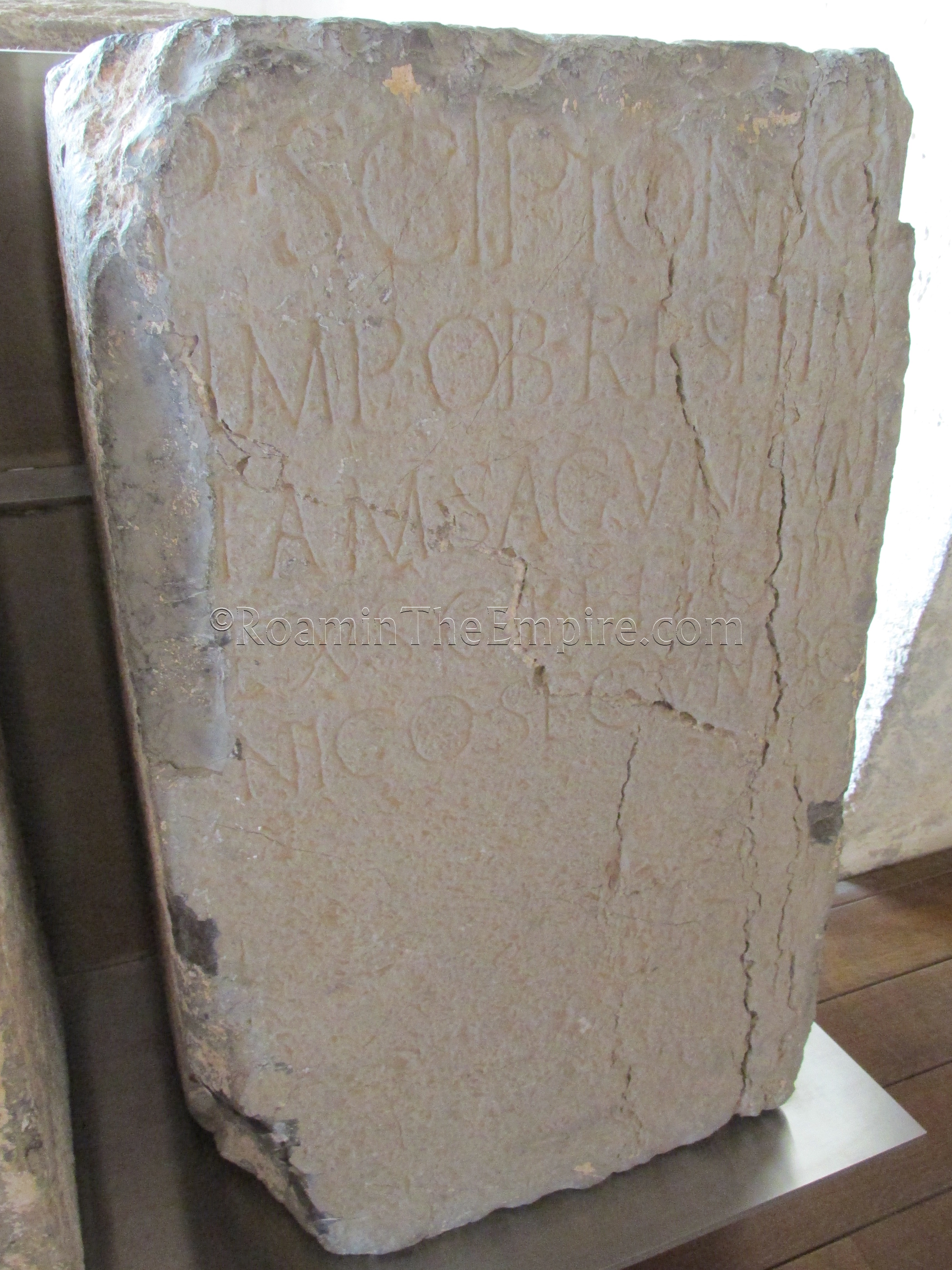

Like many of the local museums in Spain, the collection is not especially large, but it is worthwhile. It’s a two level museum, and upstairs is the typically collection of small artifacts; various bronze pieces, loom weights, ceramics, and bone objects. There’s a pretty decent collection of inscriptions, both funerary and honorific. There is a more complete version of the Publius Scipio inscription marking the rebuilding of the city following the liberation by the Romans. There’s a few larger pieces of statuary, architectural elements, some wall painting fragments, and opus sectile flooring. A few Iberian pieces, including an inscription, are also part of the collection.

It took me about half an hour to get through the museum. Again, not a large collection, but certainly worth the visit. I didn’t really come across any English, all the placards are in Spanish and Valencian, so be aware of that. Again, that seems to be pretty typical for the smaller museums in the area.

Sources:

Appian, Civil Wars, 6.2.

Curchin, Leonard A. Roman Spain: Conquest and Assimilation. New York: Routledge, 1991.

Eckstein, A. M. “Rome, Saguntum and the Ebro Treaty.” Emerita, vol. 52, no. 1, 1984, pp. 51–68.

Grummond, Nancy Thomson de. An Encyclopedia of the History of Classical Archaeology. Fitzroy Dearborn, 1996.

Hiechelheim, F. M. “New Evidence on the Ebro Treaty.” Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte, vol. 3, no. 2, 1954, pp. 211–219.

Livy, Ab Urbe Condita, 21.2, 21.6, 22.14 23.18, 24.42, 28.39, 31.7

MacKendrick, Paul. The Iberian Stones Speak: Archaeology in Spain and Portugal. New York: Funk & Wagnalls, 1969.

Pliny the Elder, Naturalis Historiae, 3.4.

Plutarch, Sertorius, 21.

Polybius, Histories, 3.6, 3.15.

Scullard, H. H. A History of the Roman world: 753 to 146 BC. London: Routledge, 1980.

Spann, Philip O. “Saguntum vs. Segontia: A Note on the Topography of the Sertorian War.” Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte, vol. 33, no. 1, 1984, pp. 115–119.

Stillwell, Richard, William L. MacDonald, and Marian Holland. McAllister. The Princeton Encyclopedia of Classical Sites. Princeton, NJ: Princeton U Press, 1976.