Most Recent Visit: June 2018.

The site of the modern-day city of Jublains, France seems to have been inhabited by the Gallic Diablintes people (also referred to as the Aulercii Diaulitae) as a domestic site as early as the late 2nd century BCE. The town of Noviodunum (also known as Noeodunum or Noiodunum, and not to be confused with the Roman fort of the same name on the Lower Danube River in present day Romania or the ancient town on the present day site of Nyon, Switzerland) seems to have grown up around a sanctuary site that developed at that location in the 4th century BCE. The settlement apparently grew to become an important town of the Diablintes at the time of Julius Caesar’s conquest of Gaul, perhaps the chief artisanal center for the Diablintes. Other than that, however, little is known about the history of the site prior to the Roman arrival.

The Diablintes seem to be among the tribes in northwestern Gaul that submitted to Caesar in 57 BCE, a group that most notably included the Veneti. Having signed a treaty with the Romans and sent hostages, the Veneti captured a number of Roman officers in 56 BCE, apparently seeking to use them to force the return of their hostages, and re-igniting warfare. Caesar notes that the Diablintes were among the tribes that allied with the Veneti against Rome in the ensuing conflict. Caesar quickly put brought the uprising to heel that same year with a definitive defeat of the Veneti navy in the Battle of Morbihan, which was followed by the sacking of the Veneti settlements and sale of the Veneti people into slavery. The Diablintes and the other allies seemed to escape harsh punishment for their part in the uprising, with the Veneti likely serving as an example to discourage further rebellion against Rome.

The extension of Roman hegemony to the area does not seem to have had an immediate effect on the infrastructure of the Gallic town, though Noviodunum seems to have increased in importance among the Diablintes at this time. The presence of the town at the crossroads of major trade routes developing with the new Roman influence seems to have hastened the growing importance of Noviodunum. During the time of Augustus, the whole of Gaul was reorganized administratively, and Noviodunum became the chief city of a semi-autonomous state of the Diablintes and was also referred to as Civitas Diablintum. During the reign of Tiberius, the town seems to have begun the process of Roman urbanization, with the town now being reconstructed on a grid pattern and the major remaining monuments being constructed from that point through to the latter half of the century. In the second half of the 3rd century CE, Noviodunum started to decline, precipitated by Germanic incursions into the territory and subsequent unrest brought on by these incursions. By the 5th century CE, Noviodunum had lost its status as the ‘capital’ of an administrative area delineated by the territory of the Diablintes, and was absorbed into a larger administrative area of the Cenomani people. The town was largely abandoned in the 6th century CE.

Though the town, and the Diablintes themselves do not figure into the historical record much, there is an interesting occurrence to note. A wooden tablet excavated in London in 1994 notes the purchase by Vegetus, the assistant slave of Montanus, who was a slave of the emperor, of a girl named Fortunata. Fortunata is noted in the text of the transaction as being of the Diablintes, and may very well have come from Noviodunum. The tablet has been theorized to date to the reign of Domitian.

Getting There: Jublains is a small town of about 700 people, and as such, the transportation infrastructure is not exactly robust. There is no train station here, though there is supposedly a bus line (ligne 12) from Mayenne to Evron (which is a stop on the Rennes to Le Mans train line) that runs via Jublains. During my visit to Jublains, I had a rental car, so I can’t speak as to the actual existence of this bus line, but it seems to make at least few stops each day (running in either direction) in Jublains. The schedule for this bus is rather complicated, but the most up to day information on it can be found at the Pays de la Loire transportation website, and the schedule can specifically be found here. There is also apparently some sort of free, on-demand bus service that works in the area through Pays de la Loire as well, and the information for scheduling that can be found at the website. The bus fare is 2 Euros and the journey time is around 15 minutes. Trains from Le Mans to Evron (and back) run several times a day, with most frequency in the morning and evening work transit times, and a few times during the day and in the evening. The travel time for direct trains is typically between 30 and 40 minutes and costs 8 Euros, while trains with connections take longer and are more expensive (scheduling information can be found here). Synching the train and bus schedule seems a rather daunting task, but there do seem to be a few points of intersection, so it certainly is possible. Jublains is also small enough that seeing everything on foot is absolutely possible, and there was available parking at the museum.

The best place to start a tour of the sites in town is at the museum, which is adjacent to the fortress. The Musée Archéologique Départemental de Jublains is located at 13 Rue de la Libération, Jublains 53160, southwest of the town center on the D129. The museum is open daily from 9:00 to 12:30 and from 13:30 to 18:00 in May, June, and September. In July and August, it is open every day between 9:00 and 18:00. From October to April it is open every day except Wednesday from 9:30 to 12:30 and from 13:30 to 17:30. Between December 15th and January 31st, the museum is closed. Entrance to the museum is 4 Euros.

As one might expect, the collection of the museum is very much centered on the Gallo-Roman archaeology of the town and surrounding areas. The majority of the collection comes from the Roman era of the town, though there are a number of objects from the pre-Roman period. Most of the pieces in the museum are rather small everyday type objects found in the excavations of the various monuments around the city, and there is a decided lack of larger statuary and objects. Much of the museum is laid out thematically with objects grouped according to the building they were associated with. Some highlights of the museum include an example of the enigmatic dodecahedron that are found throughout the empire, but mostly in modern Germany and France, some remains indicating shoe making, and a few fragments of fresco with intact graffiti.

The museum is rather small, it took a little less than an hour to get through, but given the location of the museum in a small, out of the way town of about 700 people, it really is quite a nice collection. One of the most spectacular things about the museum was the wealth of information on display; there were numerous, large information placards explaining the town, region, and the various Roman structures remaining in Jublains. These large placards had pictures and plans as well as translations of the text in English and German in addition to the French. Most artifacts also had English translations and often a lot of contextual information.

Adjacent to the museum, and accessed through the museum, is the so-called “fortress” of Jublains. The layout of this fortress-like complex is reminiscent of later defensive structures, likely earning it the moniker, but in reality does not seem to have initially been used with an overtly military function, and is apparently unique in the Roman world. This construction consists of a fortified central structure with towers, surrounded by earthen defensive works, in turn surrounded by another set of stone walls with towers. Those three primary features seem to have been constructed in stages over the course of the 3rd century CE, with the central building being constructed about 200 CE, and the earthen defensive wall and outer stone wall coming in 290 CE and 295 CE, respectively. The central building is theorized to be some sort of storehouse, though what exactly it housed is unknown. The position of Noviodunum at the crossroads of trade routes could have meant any number of goods were stored there. The location, outside of the town, and the expense that likely would have went into the construction have led to the theory that it was an imperial property, rather than local. The additional defensive measures constructed around the storehouse were likely the result of the Germanic invasions of the second half of the 3rd century CE. It is possible that at this point, the complex may have been used to serve some military function.

The outer stone wall was apparently not completely finished, which may account for the uneven and seemingly haphazard distribution of towers, before the complex was abandoned in the early 4th century CE. Though nothing has been excavated between the earthen defensive wall and the stone defensive wall, there are two bathing complexes within the earthen wall but outside the central structure. At the north corner, against the earthen wall, are the small baths, and at the south corner, again, constructed against the earthen wall, are the large baths. No date is given for construction of either of the baths, but it seems likely it was sometime after the construction of the earthen wall. The small baths are surmised to have been used by the more senior members of the administrative team of the storehouse (or if there was indeed a military presence, the higher ranking officers), while the larger baths were for the rest of the personnel. An entrance gate on the northern most part of the southeast face of the earthen wall allowed access from the intramural area into the enclosure of the earthen wall.

The west wall of the central structure includes two reinforcing constructions to the towers on either corner of that wall, constructed at the time of the earthen defensive works in about 290 CE. Between those two towers, as well as abutting the northwest and southeast towers, were cisterns, possibly part of the original construction, though no specific date is given for those. Within the central structure is a well on the west end of the building, as well as a central room, or courtyard as the documentation notes. There are a few informational signs that point out a few features of the site. The ‘fortress’ complex really is quite fascinating, and to be honest, it alone was the galvanizing factor behind adding an extra day in the Normandy region and making the 2 hour drive down to Jublains from Caen.

Just down the street from the fortress and museum, toward the center of town, is the Église Saint-Gervais-et-Saint-Protais, the town’s Catholic church. Beneath the church, excavations were carried out that revealed a Roman bathing complex. Admission to the excavations is not paid, and there are no posted hours for the excavated area, which is separate from entrance to the main part of the church on the north side below the staircase, but sticking with the hours of the museum is probably a safe bet. The baths were constructed in the 1st century CE, probably around the time that the Roman urbanization of the city began. The baths were then expanded in the 2nd century CE. Mostly what is on display beneath the church are parts of the frigidarium and tepidarium, though there are later constructions from the subsequent church present as well. After the abandonment of the baths, a church was constructed directly on the remains of the baths in the 5th century CE. An audio and lighting presentation, activated by a button on the wall by the entrance, explains the remains in some amount of detail. Outside of the church, the layout of the baths remains that extend beyond the church are traced in stone and a lighter pavement surrounding the area of the church on all sides. On the west end of the church, a few Gallic stele are also displayed.

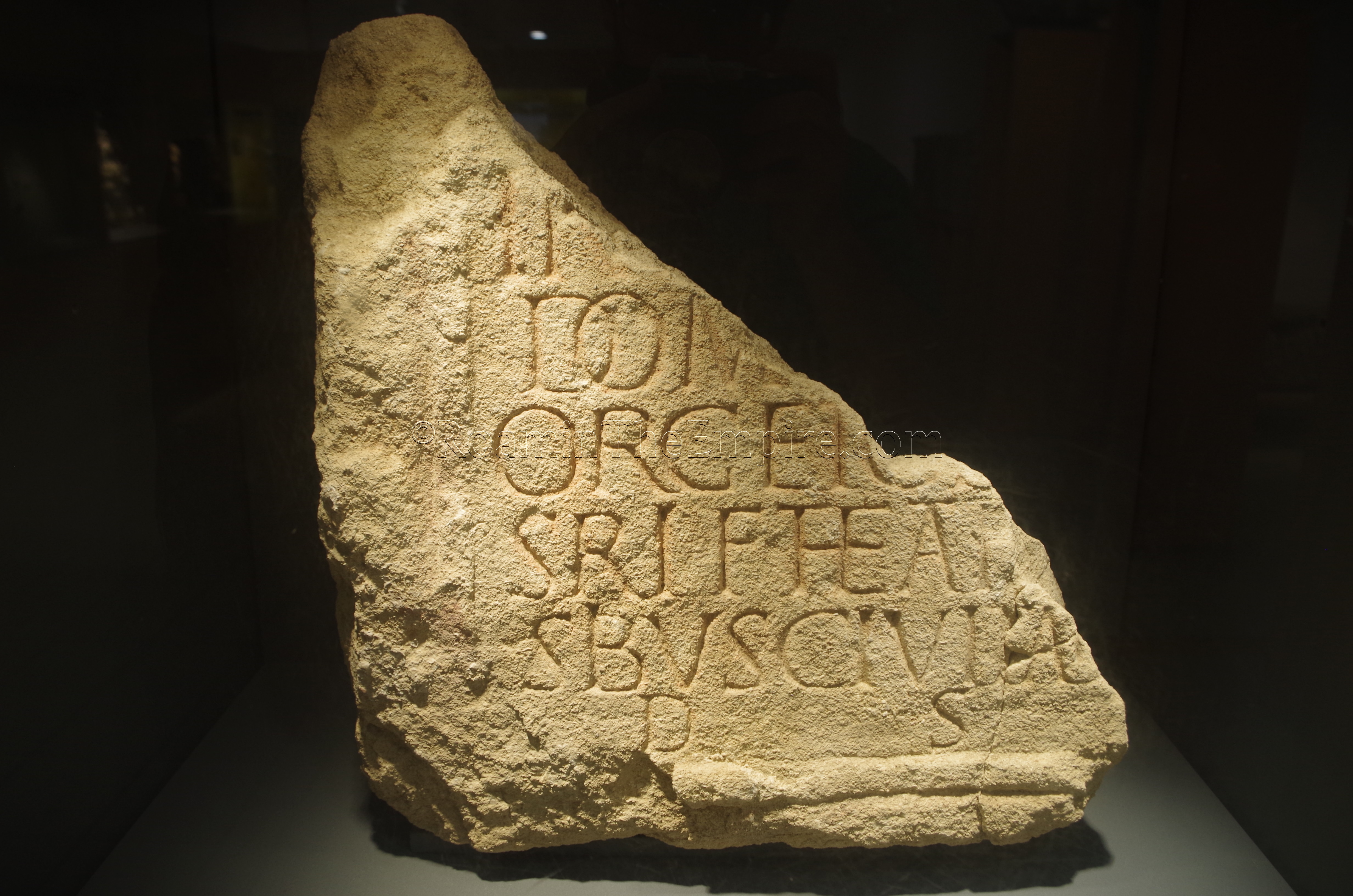

A bit further south of the church are the remains of the theater. There is no admission or entrance to the theater, so it can be visited at any time. The theater was originally constructed in the 1st century CE on a slope at the southern edge of the plateau the town is built on, and an inscription (displayed in the museum) notes its building by an Orgetorix, a member of the Diablinte tribe and probably part of the wealthy aristocratic class that governed the city. The original plan of the theater is somewhat visible in the smaller constructions remaining. It’s difficult to see from the ground, but satellite photos clearly show the very regular circular shape of the original theater, more reminiscent of the Greek style of theater, but with even more of a complete circular shape than those of the Greeks. In this phase of the theater, there was no stage wall, but rather a small circular building that served the purpose and a wooden stage. In the 2nd century, the theater was completely rebuilt on a slightly different orientation, and was given a more Roman semi-circle shape. Interestingly, the semi-circle shape is very haphazard in form, not taking a true semi-circle form and with some of the exterior wall not being a smooth circular line. Again, it’s difficult to see from the ground, but is very clear in the plans (posted on the information boards on site) and satellite imagery of the site. This version of the theater was also slightly larger than the preceding construction.

The last remains of Noviodunum on display are to the north of the town in a large, but poorly (in the sense of completion, not quality) excavated area. This area can be reached by taking the Impasse Romaine, across the street from the church, or via a parking lot a short drive outside of town on the D7. The whole area is laid out with dirt paths marking the grid of this main portion of the Roman settlement, though only a few fragments of a few insula are actually excavated in any meaningful way. Immediately to the east after entering via the Impasse Romaine, are the remains of a few buildings in what is described as an artisan quarter. The area had apparently been used during the Gallic period, but the presently exposed buildings date from the early days of the Roman settlement in the 1st century CE and are described as still retaining a Gallic style of architecture. Evidence of glass and metal working suggest the usage of the area for artisan activities.

Heading a bit further north is a large area of about 37 meters by 45 meters that appears to be under ongoing excavation. When I visited, it was covered by tarps and tires (holding down the tarps) to protect the area from rain. There was no indication of what was being excavated. Just north of that area is the area that is described as the forum. Excavations in the 19th century apparently revealed architecture here that was associated with the forum, but at present there is nothing visible, and part of the area is occupied by a 19th century building, under which there are apparently remains of the forum visible.

The only other visible remains in this area is the temple, on the very northern extent of the area delineated by the grid plan. The present temple was constructed about 66-68 CE, with major renovations and constructions also occurring in the 2nd century CE. The area seems to be the location of previous temples dating well back to the Gallic period, perhaps as early as the 4th century BCE or before, and is probably the sanctuary site that the original Gallic town group up around. The Gallic temple was dedicated to an unnamed mother goddess, and after the extension of Roman hegemony to the area and the construction of the Roman town, seems to have retained that dedication, perhaps then to a Romanized version of the goddess such as Magna Mater/Cyble.

Much of the architecture associated with the temple still remains in some form. The foundations of the exterior temple precinct wall and interior portico, along with entrances at the western and eastern side can be seen. The temple itself is situated disproportionately to the south within the precinct, rather than centered in the middle. This could possibly indicate that a second temple was originally planned to occupy the space, but was never built. The temple itself is in pretty rough shape, but parts of the cella have been pretty heavily restored, and the general form of it is visible. A roof is constructed over the temple to prevent further damage from the elements. Just east of the temple, attached to portico, are the remains of a small basin. South of that is a much larger basin within the precinct that connects to another basin just outside of the southern wall of the portico, which at this point is raised significantly above the surrounding landscape. Some structures are further associated with this basin that seem to be associated with the temple in perhaps an area for ritual ablution.

This area of the Roman remains, is, like the theater open and without admission, so it can be visited at any time and there is nothing really barring any sort of access to the area. Though much of the area is unexcavated, there are frequent signs, even in the unexcavated area, explaining about this area, specifically, as well as the town in general. As with the signs at the theater, they are in both French and English.

As a whole, Jublains and the remains of Noviodunum are pretty well presented. The presence of frequent signs in both English and French (and in the case of the museum, German) make the contextual information pretty widely accessible. Again, the ‘fortress’ is incredibly unique and well worth the visit based on that alone, though the temple is quite fascinating as well, particularly the state of preservation of some of the architecture actually associated with the temple.

Sources:

Informational signs in the museum and at the archaeological remains.

Caesar, Bello Gallico, 3.9.

Naveau, Jacques. “Jublains en Mayenne, Chef-Lieu de Cité.” Revue Archéologique, Vol. 1, 2000, pp. 220-223.

Ptolemy, Geographia, 2.7.

Rebuffat, R. “Jublains: Un Complexe Fortifé Dans L’Ouest de la Gaule.” Revue Archéologique, Vol. 2, 1985, pp. 237-256.

Tomlin, R. S. O. “’The Girl in Question’: A New Text from Roman London.” Brittania, vol. 34, 2003, pp. 41–51.