Most Recent Visit: June 2018

Over a thousand years before Avignon was the ‘City of Popes’, the focal point of a schism in the Roman Catholic church for which the city is most famous, it was the Roman town of Avennio (or Avenio). Avenio’s history, though, stretches back well before the Romans set their sights outside the Italic peninsula. The area of Avennio was in the territory of the Cavari at some point before the Roman conquest, and was considered as such by the Romans, as evidenced by later attestations of Avennio Cavarum. The 6th century CE writer Stephanus of Byzantium refers to Avennio as a city of Massalia, which is a bit unclear in scope. It is sometimes surmised that a Greek emporium called Aouennion was founded there in the middle of the 6th century BCE by the Phocaean Greeks of Massilia which later expanded to a larger settlement of the Cavari. The designation by Stephanus, though, could also just reflect the growth of the Massalian sphere of influence to include the Cavari settlement.

While Avennio remained an associated city within the territory of Massalia, which retained its independence even after Roman conquest of the surrounding area in 121 BCE, it does seem to have been subject also to Roman hegemony. In 49 BCE, when Massalia supported Pompey in Caesar’s Civil War and was subsequently besieged and taken by Caesar, Massalia retained some autonomy but lost all of its territory to Rome, including Avennio, which was given Latin rights. Sometime after Caesar’s death, perhaps as early as 43 BCE, Avennio received a colony and was given the name Colonia Julia Augusta Avennio.

Avennio doesn’t get much mention in the intervening years, but, the visit of Hadrian in the 2nd century CE results in another colonial title being given to Avennio; Colonia Julia Hadriana Avenniensis. Avennio seems to have been a relatively successful settlement; situated on the Via Agrippa between Arelate (Arles) and Vienna (Vienne) it benefitted from the trade running along that road. The Frankish and Alemanni invasions starting toward the end of the 3rd century CE, though, began to exact a harsh toll on Avennio as the city declined to a fraction of its population by the 5th century CE when it was sacked and then changed hands several times before finally being incorporated into the territory of the Burgundians.

Getting There

Avignon is pretty well connected to the rest of the region and beyond, and its proximity to the second largest city in France, Marseille, makes getting there even easier. The Aéroport de Marseille Provence is a reasonably large airport, and is probably the closest international airport to Avignon. From the airport train station, a 10 minute shuttle can be taken to Aix-en-Provence TVG where there is a direct train to Avignon TVG that takes less than 20 minutes. All told, even with average waiting times between the shuttle and the train, the journey typically takes only about an hour, sometimes a little less and sometimes a little more, and ranges in price between 14 and 31 Euros. Trains depart Aix-en-Provence TVG a few times an hour, most hours, though there are gaps in that. Detailed schedules and prices can be found on the SNCF website. Trains run from the Marseille city center on a similar schedule and take about 30 minutes, costing between about 10 and 22 Euros. Both routes run to the Avignon TVG, which is outside the Avignon city center. There are regular trains a few times an hour between Avignon TVG and Avignon Center that take just a few minutes and cost a few Euros.

Archaeological Remains

The destruction and rebuilding following the invasions in the 3rd to 5th centuries CE, and the growth of the medieval city of Avignon have left very few architectural remains from the Roman city of Avennio. All of the remaining vestiges are located in close proximity to the Palais des Papes. A few blocks to the west, on Rue Saint-Etienne between Rue de la Petite Fusterie and Rue Racine are the remains of the forum. Remains of a few arches incorporated in both the west facing wall on the south side of Rue Saint-Etienne and in the east facing wall on the north side of the street are visible. There are also some blocks on the north side of the street that appear to have come from the remains of the forum. The arches are interpreted as part of a structure, perhaps a cryptoporticus, which was used to level the sloping terrain in that area.

A few blocks south on Rue Racine, on the west side of the street, just to the north of Église Saint-Agricol, are the remains of a few structures associated with the southern extent of the forum area. The walls here, including one with a semi-circular apse-like structure, are thought to either be associated with a portico or possibly even a basilica.

The final set of visible remains of Avennio are just to the south of the Palais des Papes, at the intersection of Rue de la Peyrolerie (which runs east-west along the southern extent of the palace) and Place de l’Amirande. On the south side of Rue de la Peyrolerie, below street level, are a few arches dating to the 1st century CE. While the exact nature of the arches is not known, it is believed that they belong to Avennio’s theater.

Musée Calvet

In addition to the remaining architecture from Avennio, finds from the city (and beyond) are on display in the collections of two museums in Avignon. The first of those, the Musée Calvet, is a general art museum, of which only a portion of its collection is comprised of archaeological artefacts. The Musée Calvet is located at 65 Rue Joseph Vernet. The museum is open from 10:00 to 13:00 and 14:00 to 18:00 daily, except for Tuesdays, when it is closed. Admission to the Musée Calvet is free.

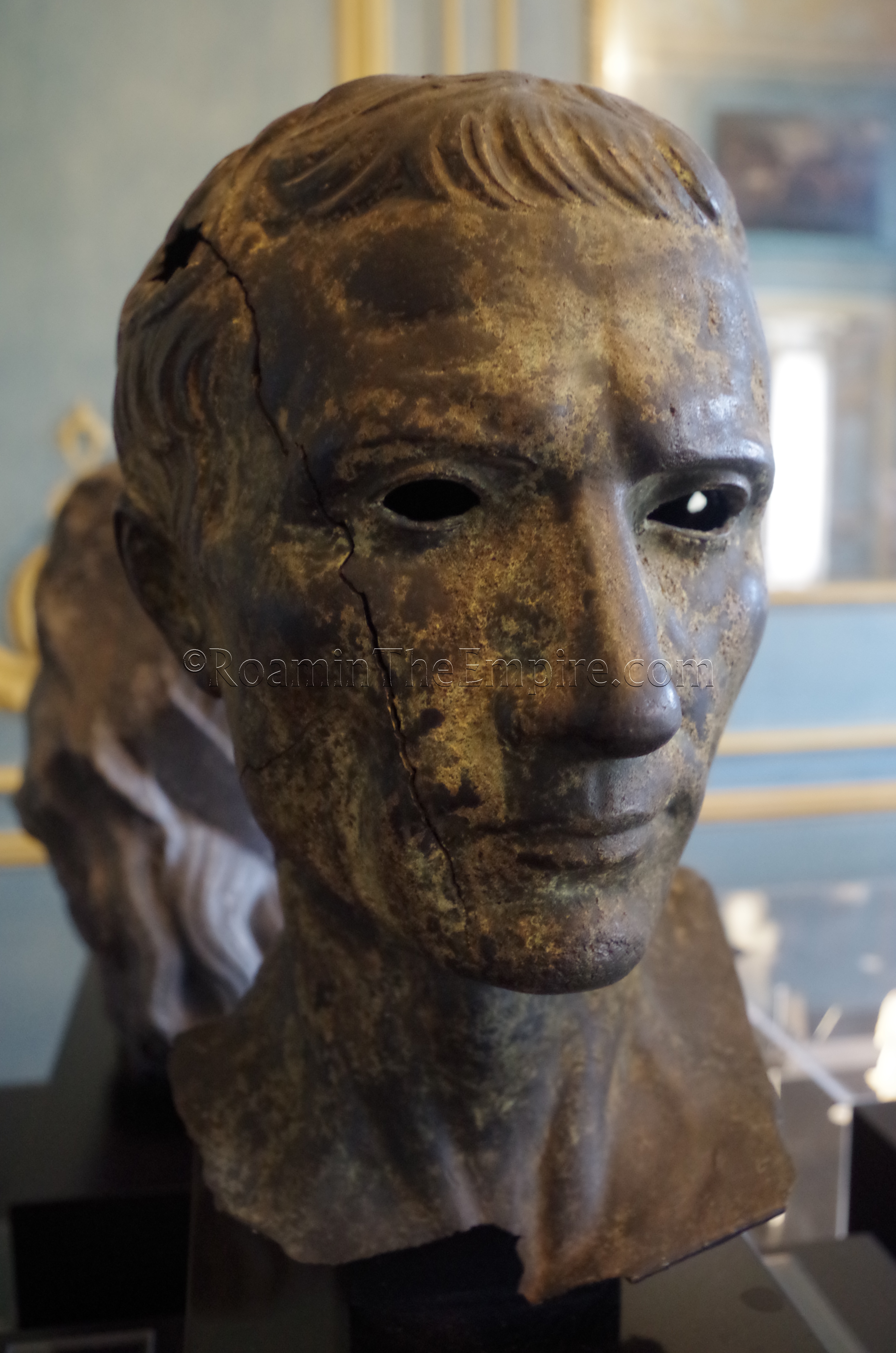

The Musée Calvet primarily serves as a general art museum, with quite a bit a bit of material from other periods. In fact, much of the Greco-Roman collection is housed in another museum in town. There is, however, a room of ancient antiquities, mostly Egyptian in origin, but also some Roman and Roman era Egypt. The amount of ancient pieces is rather small, no more than a few dozen, but, given that the museum is free, there’s no reason not to stop in and see them. There are a few portrait busts, including a bronze bust of Julius Caesar as well as busts of Alexander the Great and Serapis. The collection also features a number of smaller terracotta pieces (lamps and figures) and a few smaller bronzes. The archaeological room takes maybe a half an hour to go through, while the entire museum took me about an hour total. Again, even though it’s a rather small collection at the Musée Calvet, being free, there’s no reason to not stop in and see it if there are no time constraints.

Musée Lapidaire

A few minutes’ walk away is the Musée Lapidaire, the archaeological repository of the Calvet collection. Housed in a Baroque chapel, the Musée Lapidaire is located at 27 Rue de la République. The museum is open from 10:00 to 13:00 and 14:00 to 18:00 year round from Tuesday to Sunday. It is closed on Mondays. Admission to the Musée Lapidaire is free.

The collection at the Musée Lapidaire is fairly substantial. As the name suggests, the collection is primarily larger stone objects in the form of statuary, inscriptions, and stele. A few mosaics are even among the artefacts housed in the museum. There are quite a few funerary objects, including mostly inscriptions and architectural elements, but also a few sarcophagi. While many of the objects are of a more local provenance, there are also artefacts from far away as Greece and Turkey assembled in the collection. In addition to the Roman pieces, which make up the bulk of the collection, there are a number of Greek artefacts as well as a few pre-Roman Celtic objects.

Some of the highlights among the collection on display at the Musée Lapidaire are a 3rd century CE mosaic of Hercules and Hesion, a high relief of the Gallic god Sucellus, and a colossal statue of Livia. Among the Greek objects is a statue of Athena Parthenos. Perhaps the most famous object and centerpiece of the collection is the 2nd-3rd century CE fragment of a funerary relief that depicts workers hauling a barge, which is featured prominently in the center of the museum, near the entrance. It took me a little under an hour to see the entire museum. Like the Musée Calvet, the price is hard to beat. Since the Musée Lapidaire essentially acts as Avignon’s archaeological museum, between the collection and the free admission, there’s really no reason not to visit, even if one can’t devote a full hour to it. A quick 20 minute run through looking at some of the highlights is time well spent.

The remains of Roman Avennio can easily be seen in just a couple hours, as everything is centered in a very compact area. In my case, I used Avignon as a sort of home base to see other sites and cities in Provence and saw all these the afternoon I arrived, before I picked up my rental car, with time to spare.

Sources:

Bromwich, James. The Roman Remains of Southern France: A Guidebook. London: Routledge, 1996.

Christol, Michel and Marc Heijmans. “Les colonies latines de Narbonnaise: un noveau document d’Arles mentionnant la Colonia Julia Augusta Avennio.’” Gallia, Vol. 49, 1992, pp. 37-44.

Drake, Joseph H. “Studies in the Scriptores Historiae Augustae.’” The American Journal of Philology, Vol. 20, No. 1, 1899, pp. 40-58.

Ebel, Charles. “Southern Gaul in the Triumviral Period: A Critical Stage of Romanization.’” The American Journal of Philology, Vol. 109, No. 4, 1988, pp. 572-590.

Pliny, Naturalis Historia, 3.36.1.

Pomponius Mela, De Chorographia, 2.75.

Ptolemy, Geographia, 9.

Smith, William. Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography. Walton & Murray, 1870.

Strabo, Geographica, 4.1.11.