Most Recent Visit: June 2018

As has been discussed in previous posts, there are a number of sites that would be categorized as miscellaneous; not associated with any major site that would warrant a full post to itself, but also very much worth visiting. A number of these sites spring up along the path of the Via Domitia, and in particular a stretch of the Via Domitia between Cabellio (Cavaillon) and a little beyond Segustero (Sisteron).

After the pacification of several of the major hostile Gallic tribes in southern Gaul by Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus and Quintus Fabius Maximus Allobrogicus in 121 BCE, the former constructed the Via Domitia in 118 BCE to link Gallia Cisalpina with Hispania. One of the primary reasons for the pacification of the area may have, in fact, been in securing this land route of Italy with Hispania. Because of his involvement, the road bore the nomen of Ahenobarbus.

Getting There:

Running east from Cavaillon through the Parc Naturel Régional du Luberon, the route of the Via Domitia follows roughly the D900/D4100 road, before swinging north along the route of the A51 highway, which follows the Durance River up through Sisteron. As many of the sites are in relatively rural settings, a personal vehicle is really the only way to see the itinerary. Apt and Sisteron may be reachable by public transportation, but aside from those locations, it would be difficult to see many of the other sites mentioned here.

The first of the monuments encountered is the Pont Julien, about 8 kilometers west of Apta Julia (Apt), near the village of Roussillon. The bridge carried the Via Domitia over the Cavalon River and was constructed in 3 BCE, probably replacing an older wooden bridge that served the road in the 100 or so years prior to the construction of the Pont Julien. Some cuts in the rock on the east side of the bridge (north bank) may be associated with the earlier wooden bridge at this location. Up until 2005, the bridge was open to road traffic, but with the construction of the parallel road bridge to the east, is now open to only pedestrian/bike traffic. Though they are mostly gone, there are the remains of breakwaters on the east side of the bridge. The modern name of Pont Julien is derived from the proximity to Apta Julia, the next stop on the itinerary.

The general site of Colonia Apta Julia Vulgientum was originally occupied by a settlement of the Vulgientes, but was destroyed in the Roman conquest of the area about 123 BCE. The site seems to have remain mostly unoccupied until about 45 BCE, when a colony was founded there by Julius Caesar. Other than those two events, though, not much is known about the history of the city. Apta Julia was the location of the tomb of Hadrian’s favorite horse, Borysthenes, who died there during a boar hunt in 121 CE. Unfortunately, many of the better remains of Apta Julia are difficult to access. The Musée d’Histoire et d’Archéologie, located at 27 Rue de l’Amphithéâtre is only available to visit by reservation and only for schools or groups. In addition to housing the majority of the archaeological collection for the city, the basement also contains the remains of the theater. There are also Roman remains and inscriptions in the crypt of the nearby Cathédrale Sainte-Anne, but that was likewise closed, apparently for a lack of ability to monitor the area.

There are a few things in Apt able to be visited. In Place Jean Jaurès are the remains of the forum of Apta Julia. The remains amount to a few walls displayed in a recessed part of the square. There is no accompanying information and the remains do not look well taken care of, as there is nothing limiting access and several of the walls had spray painted graffiti on them. Nearby is the Musée d’Apt at 14 Place du Postel. The museum is open most of the year Tuesday to Saturday from 10:00 to 12:00 and 14:00 to 17:30. In July and August the museum is also open on Mondays and is open an hour later in the evenings. It is closed in January. Admission is 5 Euros. For one interested strictly in archaeology, there are only a few artifacts here, and the admission is hardly worth that. There are other exhibits related to the area, though, and it’s a relatively nice little museum. Even going through the entire thing, however, and not speaking French, I found the price to be a little steep.

Continuing along the Via Domitia is the town of Catuliacia (modern Céreste). Just to the north of town, spanning the Encrême River, is a bridge referred to as the Pont Romain de la Baou. Despite the name, this is not a Roman bridge, but rather is an 18th century CE construction. While there does appear to have been a Roman bridge crossing the Encrême here, the bridge that stands here today was a much later construction.

While traveling along the route of the Via Domitia, there were a few signs along the way that pointed to places of interest associated with the road (often vague generic signs that just noted Via Domitia), often down roads that didn’t seem suited for travel by most cars. One, however, near the town of Mane proved to be fruitful. Located on a small road off the D4100 is a boundary stone that may have marked the place of station along the Via Domitia, and would have been used to help plan land registry in the area. Known locally as the Bourne de Tavernoure, there is a small informational sign in French nearby. The stone sits just off to the side of a modern road, and so there is no limited access and it can be accessed at any time.

Up the road a short distance is the town of Mane and the nearby Pont Sur La Laye, or Pont Roman de Mane. Spanning the Laye River running south of the modern town, the actual dating of the bridge is a matter of some debate. Some sources place the construction of the Pont Sur La Laye at the 2nd or 3rd century CE, while others suggest that the construction dates to the 11th century CE. Still other evidence suggests that two of the three arches were constructed as late as the 17th century CE. In reality, it seems likely that there is a bit of truth to all of the dates, with the bridge perhaps originally being constructed at the location in the Roman era, but undergoing heavy renovations and reconstructions in the intervening centuries. It should be noted, when visiting, the turnoff to the bridge looks like a private road associated with the hotel right next to the bridge, but it is indeed a public road and there is a small public lot next to the hotel where one can park to visit the bridge.

Continuing on to the east, one encounters the Durance River and the route of the Via Domitia continues north at approximately the course of the A51 and the parallel D4096. A few kilometers south of the town of Ganagobie is another of the previously mentioned Via Domitia signs that I encountered without previous knowledge and was able to follow. This one lead to the Pont de Ganagobie, a Roman bridge on which the Via Domitia crossed the Buès River. After taking the turnoff, be sure to follow the road to the left, not the right, which leads up to the Abbaye Notre Dame de Ganagobie. The single arch bridge seems to have been constructed about 2 CE, though some analysis puts it a bit later in the 2nd century CE. The sign that led to this bridge also noted ‘Mosaiques Romanes,’ but the term ‘Romanes’ can refer to something either of the Roman age or being Romanesque, and the mosaics this sign points to belong to the latter categorization and are located in the nearby Abbaye Notre Dame de Ganagobie.

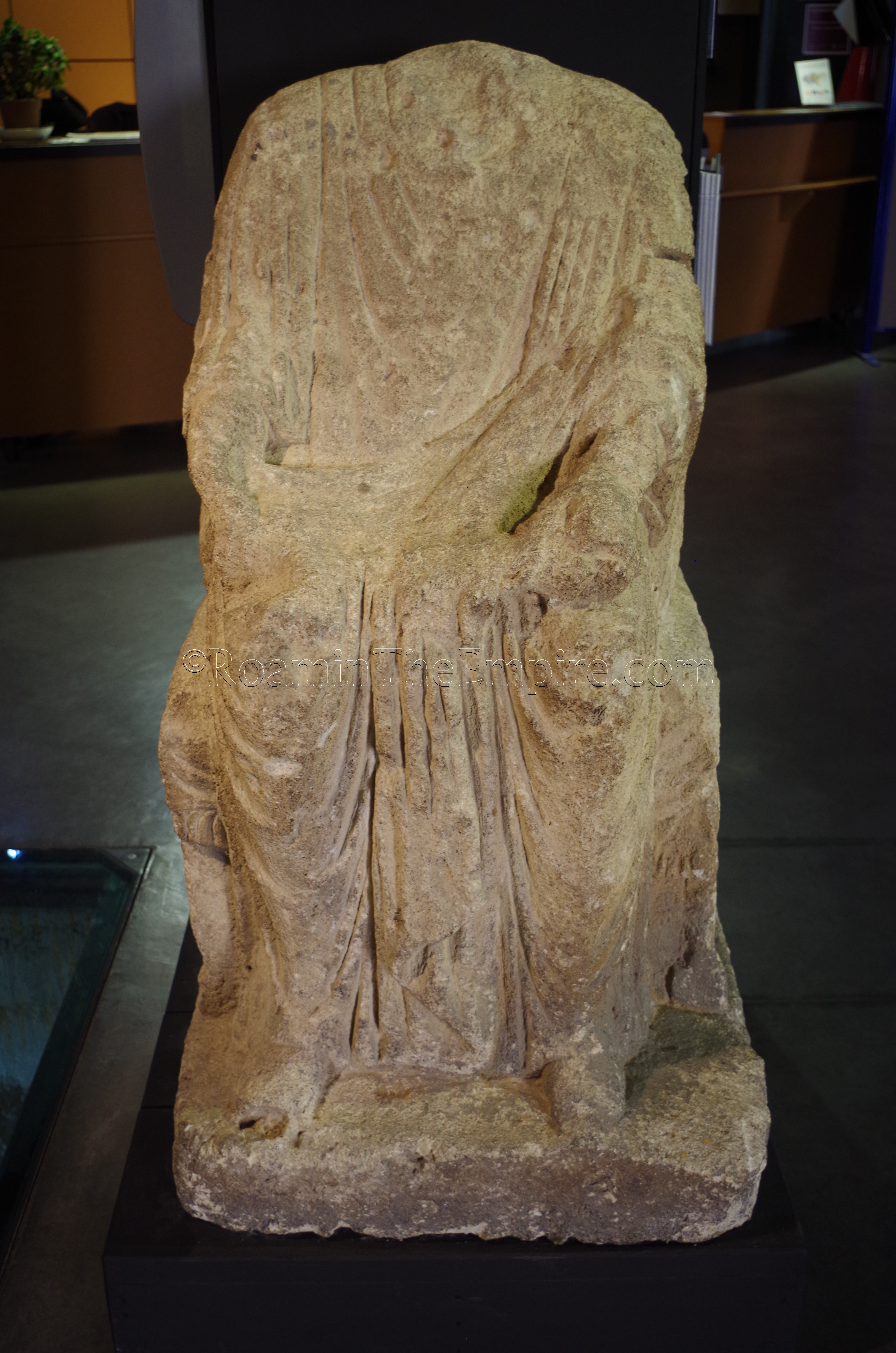

A bit further up the Durance River is Sisteron, the modern town at the spot of Segustero. Nothing really remains of ancient Segustero to see, but there is the Musée-Gallo-Romain de Sisteron in the historic center. Located at 8 Rue Saunerie, the opening hours are extremely convoluted, and it’s better just to check the official website here. Admission is free. The museum is relatively small, and nearly all of the artifacts are funerary in nature, related to tombs found in the area. It took me less than 15 minutes to go through the museum (after spending about an hour waiting for it to open), but given the price, it’s certainly worth checking out. That is, of course, unless one has to wait a significant amount of time waiting for the weird opening hours to kick in, then the time may better be spent elsewhere.

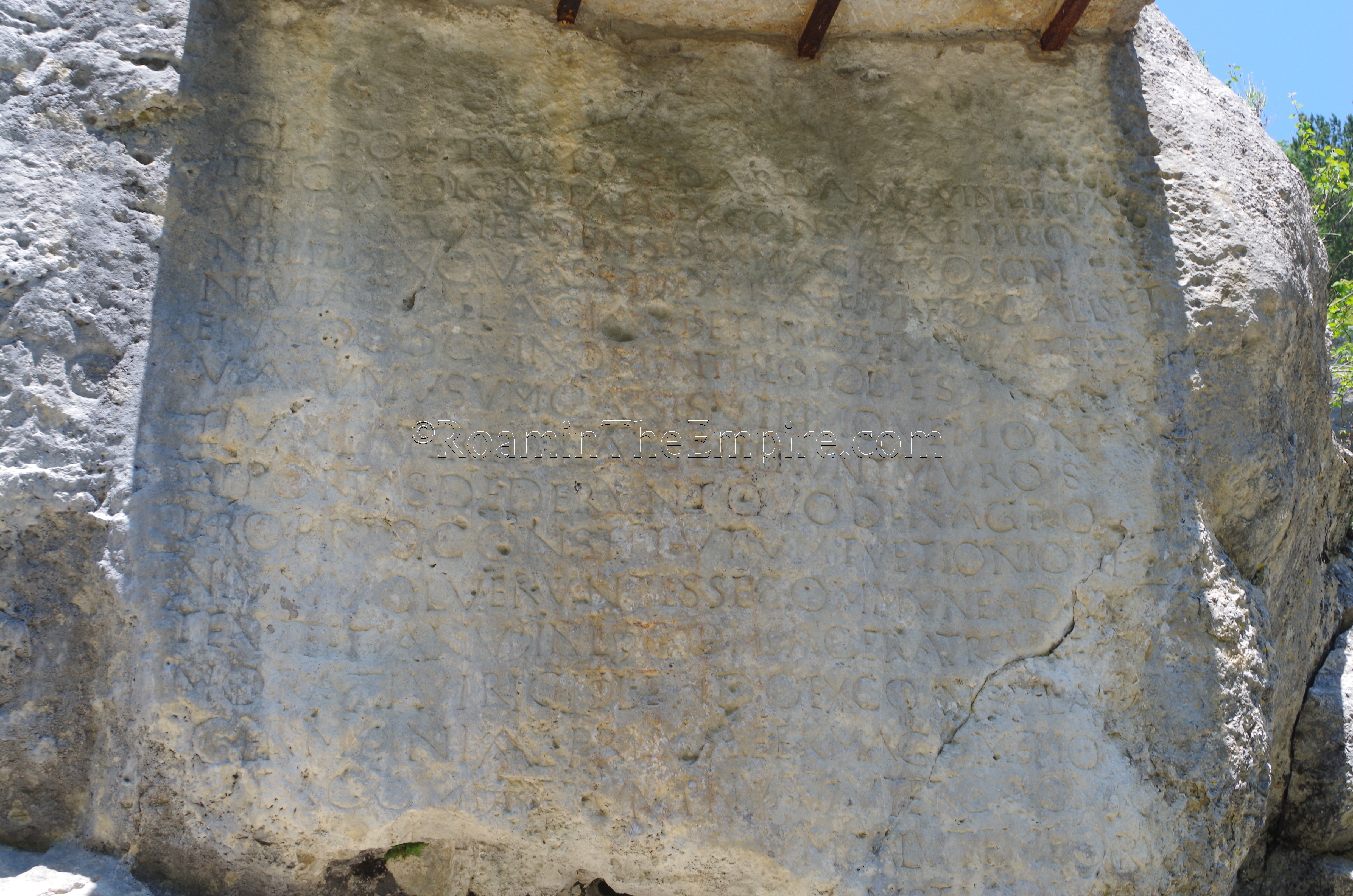

The last site along this itinerary isn’t actually on the Via Domitia. Located along the D3 in the mountains northeast of Sisteron is the Pierre Ecrite, an inscription carved into the living rock alongside the road. The inscription dates to the early 5th century CE, and was commissioned by Gaius Posthumus Dardanus, who was the Praetorian Prefect of Gaul twice in the period between 401 CE and 413 CE. The inscription also mentions his wife, Naevia Galla, and how he constructed a road through the area to Theopolis (City of God) which seems to have been some kind of fortified compound or religious retreat that Dardanus established amid the turmoil consuming the empire at the time. Though no archaeological evidence of this Theopolis has been found, it is believed to be a bit further up the road near the present-day town of Saint-Geniez. There is a small parking area just before (to the west) arriving at the inscription, and there are a couple informational signs next to the inscription, mostly in French but with some English translations.

The total driving time for the itinerary is about 2 hours one-way, or 4 hours round trip. Given that none of the stops are especially time consuming, it’s certainly an itinerary that can be accomplished in one day

Sources:

Bromwich, James. The Roman Remains of Southern France: A Guidebook. London: Routledge, 1996.

Smith, William. Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography. Walton & Murray, 1870.

Stillwell, Richard, William L. MacDonald, and Marian Holland. McAllister. The Princeton Encyclopedia of Classical Sites. Princeton, NJ: Princeton U Press, 1976.