History

Located at the mouth of the present-day Marecchia River (the Ariminus in antiquity) is the Italian Adriatic seaside resort town of Rimini, successor of the Roman settlement of Ariminum. The area seems to have been under the control of the Etruscans until about the 6th century BCE, when the Etruscans were dislodged from the area by the Umbri. The Umbri, in turn were driven out of the area by the Gallic Senones, who along with several other Gallic tribes migrated and settled in Northern Italy. From that point, the Senones were in almost constant conflict with both the Etruscans and Romans, and were the leading tribe involved in the Battle of Allia and subsequent sack of Rome around 390 BCE. The Senones also joined the Etruscans and Umbri to aid the Samnites in the Third Samnite War, but were defeated at the Battle of Sentium in 295 BCE. This opened the door for a final invasion of the Senones lands in Northern Italy in 283 BCE, in which they soundly defeated the Senone Gauls and extended Roman hegemony over their former territory.

The Latin colony of Ariminum was founded in 268 BCE, named after the river. The settlement was of particular strategic importance as it stood in the primary coastal route running south from the Padus (Po) Valley between the Apennine Mountains and the Adriatic Sea. It would serve as both a defensive point and a staging area for Roman operations further north. In 220 BCE, Ariminum became the terminus of the Via Flaminia from Rome, and few years later in 187 BCE, became the starting point of the Via Aemelia which ran northward to Placentia (Piacenza). In 132 BCE, a second northern road, the Via Popilia, was constructed along the coast with Ariminum as the origin. The confluence of so many roads at the city and its location at the mouth of the Ariminus cemented its importance as a Roman port on the Adriatic.

Ariminum is noted as remaining loyal to Rome throughout Hannibal’s campaigns in Italy during the Second Punic War, and it serves as a base of operations for various aspects of the Roman campaigns in Italy during the war. During Sulla’s Civil War, the city threw its support behind Marius, and was subsequently besieged and sacked by Sulla’s forces around 89 or 88 BCE. He would later reconstruct the walls of the city, though. It was also around this time when Ariminum was granted municipium. When Julius Caesar marched on Italy in January of 49 BCE, Arminum was his first stop after crossing the Rubicon (probably at nearby Savignano sul Rubicone) and the location at which he addressed the troops of Legio XIII Gemina. In 41 BCE, land in Ariminum was confiscated and granted to veterans. Octavian employed the city as a headquarters during his Illyrian campaigns and also granted the city colonia status around this time.

During the imperial period, Ariminum was a stronghold of the Flavian faction in the civil war of 69 CE. The 2nd and early 3rd centuries CE saw especially fruitful agricultural production in the hinterland of the city, which became especially notable for wine production. Ariminum suffered in the various invasions starting in the mid to late 4th century CE, but did maintain some semblance of stability due to its proximity to Ravenna in the waning years of the Roman Empire and the rise of Ostrogothic hegemony.

Getting There: Rimini is the largest city in the popular stretch of Adriatic beaches between Ravenna and Ancona, and as such is pretty well connected to the rest of the country, particularly in the busy summer season. The city is served by the Aeroporto di Rimini/San-Marino – Federico Fellini to the south of the city, which hosts flights from about a dozen other European cities in the summer, and a handful year round. A more reliable airport in the off-season might be the Aeroporto di Bologna – Guglielmo Marconi. Trains depart from Bologna to Rimini fairly regularly (upwards of twice an hour much of the day) even in the off-season. The trip ranges from 53 minutes to about 2 hours depending on the train, and fares start at about 10 Euros one way. If traveling by personal vehicle, a lot just to the north of the Tiberius Bridge is an affordable, accessible, and convenient place to park.

Ponte di Tiberio

The first stop on the tour of Ariminum is the Ponte di Tiberio, which originally carried the Via Aemelia over the Ariminus (Marecchia) River. Now it spans a canal that ends a short distance past the bridge after the Marecchia River was diverted northward and the original course turned into a park. The bridge owes its name to being completed in 21 CE during the reign of Tiberius, though it was started under Augustus and is sometimes referred to as the Augustus Bridge for this reason. Monumental inscriptions still present on the interior of the parapets note the contribution of both emperors toward its construction.

The bridge was constructed of Istrian marble over the course of 7 years, having been started in 14 CE, not long before Augustus’ death. Decorative faux niches adorn both sides of the bridge, with brick breakwaters facing to the west. The bridge carries traffic over the river even today, and it was the only bridge on the Marecchia that was not destroyed by retreating Germans in 1944. It was supposedly fitted with charges that malfunctioned and did not explode, sparing the bridge the fate of many other Roman bridges in Northern Italy in 1944-45 (see Verona).

Museo della Città and Domus del Chirurgo

From there it is a short walk to the Museo della Città, located at Via Luigi Tonini 1. The museum is open in the summer (June 1 to August 31), Tuesday to Sunday from 10:00 to 19:00. The rest of the year it is open Tuesday to Friday from 9:30 to 13:00 and 16:00 to 19:00. Saturdays and Sundays it is open continuously from 10:00 to 19:00. The museum is closed on Monday year round. Admission is 7 Euros and includes entrance to the nearby Domus del Chirurgo archaeological area.

The Museo della Città is not a dedicated archaeological museum, and has exhibits and collections not associated with archaeology, but it does have a significant archaeological collection with some fantastic pieces. A number of small finds and ceramics from tombs dating back as far as the 13th century BCE make up part of the collection. There is a section of the museum devoted to the Domus del Chirurgo, with a few rooms reconstructed. The titular surgical instruments from the Domus del Chirurgo are on display along with some fragments of wall paintings from the archaeological area.

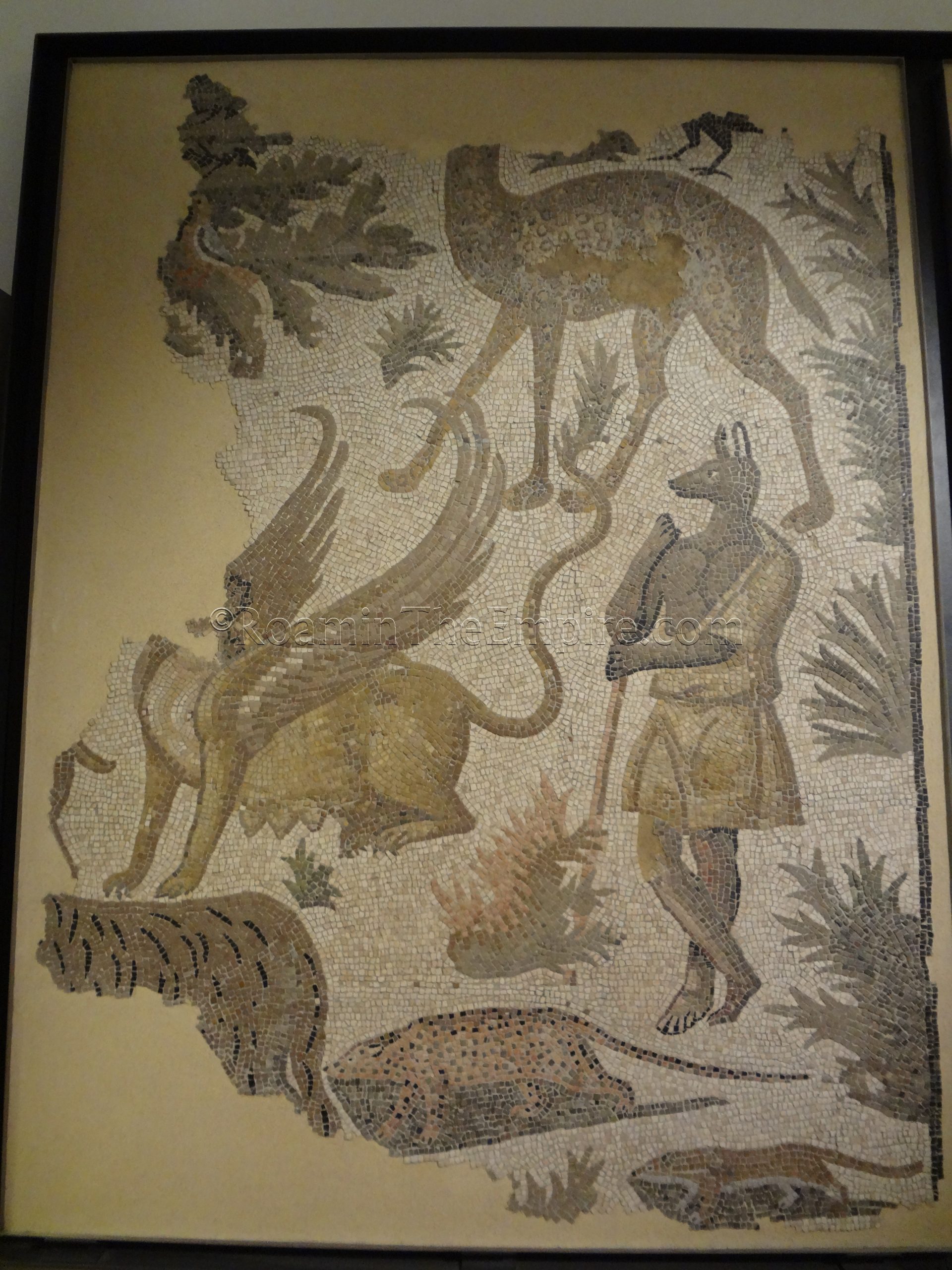

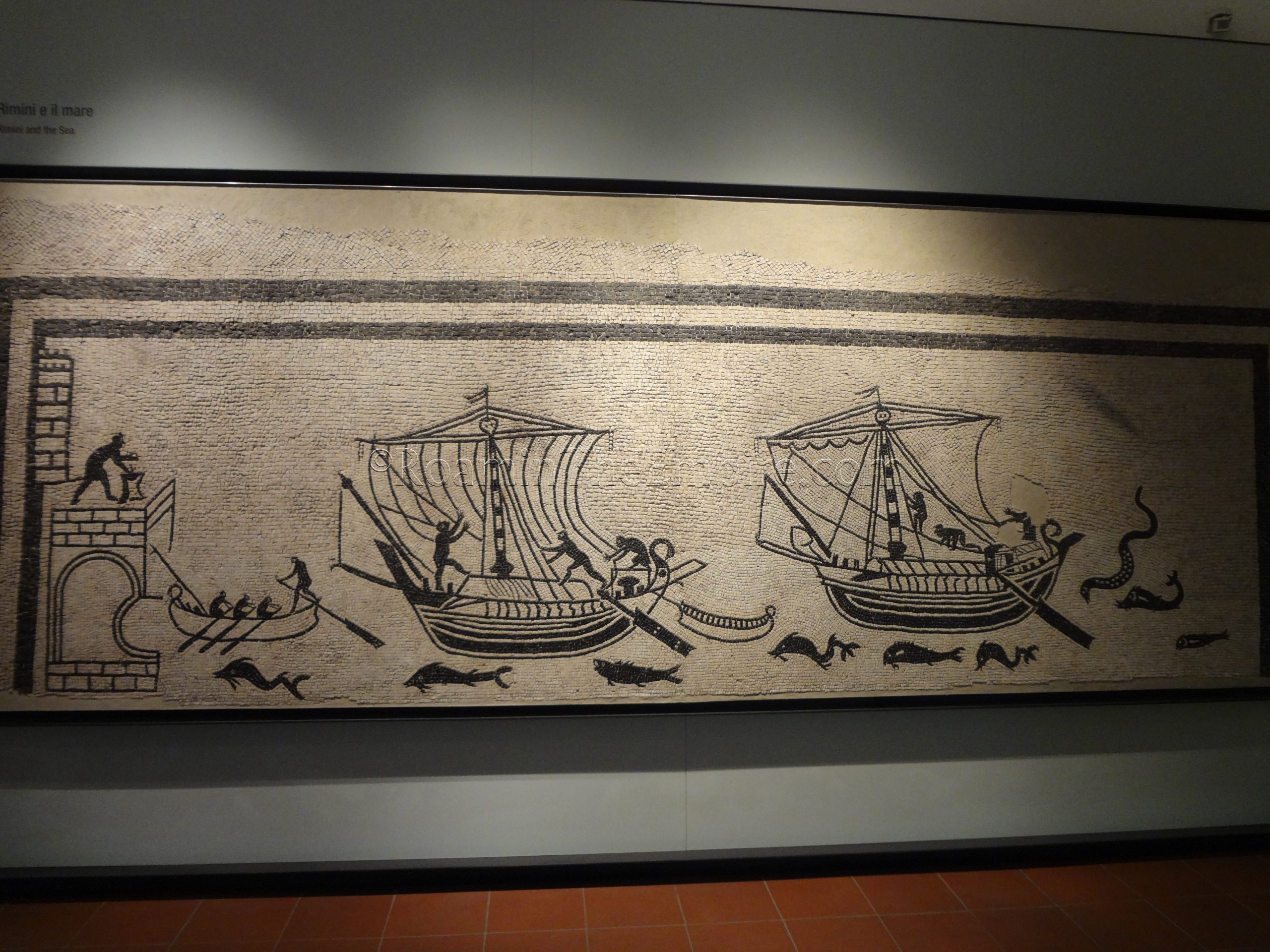

A number of mosaics are on display, many in a great state of preservation, if not a little incomplete in some instances. One, in particular, depicts Anubis surrounded by African animals, though unfortunately some of the mosaic is missing. Another depicts a harbor scene. There are quite a few figural and geometric mosaics present. The courtyard hosts a lapidary with a few dozen inscriptions, including one with Domitian’s name erased from it in damnatio memoriae.

The museum is fairly sizable, it took me about an hour and a half to get through it. There is not much in the way of information in any other language than Italian. A few of the larger informational cards had English translations, but the information for most objects did not.

Just to the south of the museum, in Piazza Luigi Ferrari is the Domus del Chirurgo, the Domus of the Surgeon. This archaeological area has the same hours as the museum and is a part of the same (compulsory) combined ticket. One can’t buy a separate entrance to either. Named as such for the collection of surgical instruments found in one of the rooms (and displayed in the museum), this residence seems to have been built in the late 2nd century CE on the spot of a previous residential building. A fire destroyed the domus in the mid to late 3rd century CE, possibly related to Germanic raids in the area at the time. The quick demise helped preserve some elements in the house. A building possibly associated with a palatial estate was constructed sometime after the fire (perhaps the 5th century CE), and which was abutted by a reworked section of the city walls constructed shortly after the fire. One of the mosaics from this building is also preserved. Burials from an early medieval necropolis are scattered throughout the house.

One of the big draws for this site is the in situ mosaics. A raised walkway takes visitors around the site. Unfortunately, some of the better mosaics are not very visible from the walkway. The Orpheus mosaic in one of the rooms is kind of distantly visible. There is not much in the way of context at the site. A few general informational boards (with English translations) give some broad information about the site, but, there isn’t much to explain the different rooms and the layout of the house. But, a lot of fantastic mosaics are easily visible and its overall a pretty interesting archaeological area. I just wish the walkway afforded better views of the Orpheus mosaic and there was more on-site information.

Forum Area

A five minute walk to the south approaches the area of the ancient forum, which was located at present-day Piazza Tre Martiri. Just north of the piazza was the location of the theater. Though there doesn’t seem to be any visible remains of the theater at this spot, a courtyard accessible at Corso d’Augosto 115 preserves the shape of the theater in the surrounding buildings.

At the northern part of Piazza Tre Martiri is a modern statue of Julius Caesar, marking the location (the ancient forum of Ariminum) where he addressed his troops following the crossing of the Rubicon. A 16th century inscription also commemorates the event on the east side of the piazza where Via IV Novembre intersects with the piazza. A small 6×3 meter section of the forum has been excavated in the western part of the piazza. Some of the forum paving stones, limestone quarried from the area of San Marino, and some brickwork from a monument are visible. It is an open area sunk into the modern piazza and is visible and accessible any time. A small informational sign in Italian and English explains the remains.

Another similar excavation is present just east of Piazza Tre Martiri, about 50 meters down Via IV Novembre (right in front of Via IV Novembre 18). Here, a 10×3 meters stretch of the cardo maximus has been excavated as it approached the forum. The brickwork of a 1st century CE building that faced the road is also visible on the south side of the road, farthest from the adjacent modern buildings. Like the forum remains, this is open air and visible at any time. A small informational sign in English and Italian is also posted nearby.

Gates and Amphitheater

The final few sites are on the outskirts of the historic center, either part of our outside the wall of the Roman Ariminum. About 5 minutes southwest out of Piazza Tre Martiri on Via Giuseppe Garibaldi, along the path of what would have been the southern spur of the cardo maximus out of the forum, is the Porta Montanara. The Porta Montanara was constructed in the 1st century BCE as part of Sulla’s restoration of the walls and marked the southern terminus of the cardo maximus. The gate was originally a double archway with one side being enclosed by modern buildings and one continuing to function. During World War II, the exposed arch was destroyed, and what stands today was actually the previously enclosed part of the gate. It is near, but not in its original location. There is a small informational sign in English and Italian and the gate is in a public square, accessible at any time.

A few minutes’ walk from the Porta Montanara, located in the green space amid a business and residential complex off Via Circonvallazione Meridionale, is a tank used for the clay settling in a production area. The tank was part of a residential and production facility for clay working that was built during the reign of Tiberius and functioned until the end of the 3rd century CE. The bottom of the tank is finished in opus spicatum. It’s not in its original location, but was rather moved to a space it could be displayed with the construction of the surrounding buildings. The tank is in a public area and so is accessible at any time without restrictions. Like many of the other monuments in the city, there is a small informational sign in English and Italian posted nearby.

Another short walk away, to the northeast, is the Arco di Augusto, the Arch of Augustus. The arch, which was located at the east end of the decumanus maximus functioned as the east gate of the city after its construction in 27 BCE. It also marked the terminus of the Via Flaminia and the start of the Via Aemelia; the inscription (remnants of which are still present on the exterior façade) notes the improvement of the Via Flaminia and other roads in Italy by Augustus. Clipei with images of Jupiter and Apollo decorate the exterior façade, while the interior sports images of Neptune and Roma. Casts of these can be seen in the museum.

Like the Tiberius Bridge, the arch was faced in Istrian marble, and it would have originally been topped by a bronze equestrian or quadriga statue of Augustus. Some small remnants of the Republican era walls flank the arch; the stretches of brickwork walls nearby date to a later period. The arch is in a public space that is always accessible without admission. There is a small informational sign adjacent to the interior of the arch.

The final stop is a bit of a walk away on the extreme eastern edge of the historic center; the Anfiteatro Romano. Only a small portion of the amphitheater is exposed on the northeast side, though the shape of the entire structure is visible in the street plan of the area with Via Vezia tracing the outline. Constructed during the time of Hadrian, there is no access to the remains, they are fenced off and can only be viewed from the outside along an exterior pathway. It had a capacity of about 10,000 spectators, and only functioned for about a century before the barbarian incursions necessitated the incorporation of the structure into the city’s defensive fortifications.

The remains of Roman Ariminum can pretty easily be seen in a half a day. Since only the museum and adjacent domus are admission dependent, there’s a lot of flexibility in visitation of everything else. Those monuments really aren’t very time consuming either.

Sources:

Appian. The Civil Wars, 1.8.

Cicero. Pro Caecina, 35

Grant, Michael. A Guide to the Ancient World: A Dictionary of Classical Place Names. New York: Barnes & Noble Books, 1997

Livy. Ab Urbe Condita, 21.15, 24.44, 27.7, 28.38, 29.5, 30.1, 31.10, 32.1, 34.45, 39.2, 41.5.

Pliny the Elder. Naturalis Historia, 3.19.

Plutarch. Life of Caesar, 32.

Polybius. Historiai, 2.21.

Stillwell, Richard, William L. MacDonald, and Marian Holland. McAllister. The Princeton Encyclopedia of Classical Sites. Princeton, NJ: Princeton U Press, 1976.

Strabo. Geographika, 5.1.

Tacitus. Historiae, 3.41.