Most Recent Visit: August 2021

Situated on the south bank of the Danubius (modern Danube River), the area of Carnuntum was originally inhabited by the Illyrian-Celtic Boii, who had an oppidum on the hill where the Hainburg Castle now resides, a few kilometers away from the military camp of Carnuntum. The name probably derives from an Illyrian word, though Ptolemy claims that the indigenous name of Carnus was of Greek origin. The name may also derive from that of the neighboring population, the Carni. When the area was brought under the control of Rome with the conquest of Pannonia in 12 BCE, the Boii settlement seems to have moved from Hainburg to the area of modern Petronell-Carnuntum and would form the basis of the civilian settlement of Carnuntum.

The military camp of Carnuntum, centered in modern Bad Deutsch-Altenburg, seems to have first been established around 6 CE, when it was used as a base of operations for Tiberius’ campaigns against the Marcomanni king Maroboduus. At that time, the castrum was referred to as Locus Norici Regni as it was then located in the province of Noricum, though shortly after it was moved to Pannonia. A stone castrum was apparently built while Tiberius was operating at Carnuntum. Though Tiberius was forced to conclude a truce and withdraw to attend to a revolt elsewhere, Legio XV Apollinaris was transferred from Emona (modern Ljubljana) to Carnuntum in 14 CE. This was apparently part of a strategy to make Carnuntum the key point and center of the stretch of the Limes Pannonicus between Vindibona (modern Vienna) and Brigetio (modern Szőny) as a castra legionis.

During the reign of Claudius, around 50 CE, an auxiliary cavalry camp was constructed between the civil and military settlements, just outside of modern Petronell-Carnuntum, to further bolster the defensive capabilities in the area. Additionally, Carnuntum seems to have served as a base for the Classis Pannonica around this time. The build up was ostensibly to deter the spillover of a conflict between Germanic groups on the other side of the Danubius from reaching Roman territory in Pannonia. The civic settlement of Carnuntum was important as the major amber trading route from the Baltic crossed over the Danubius and into Roman controlled lands at Carnuntum, making Carnuntum a major center for trade of the material.

Legio XV Apollinaris was detached from Carnuntum in 62 CE to participate in campaigns farther East. To take their place, Legio X Gemina was based in Carnuntum in 63 CE. During the brief reign of Galba in late 68 CE, Legio VII Gemina (also called Galbiana) was raised in Hispania and was transferred to Carnuntum, while Legio X Gemina was transferred to Hispania. Legio VII remained in Carnuntum until 71 CE, when Legio XV returned and the castrum was rebuilt shortly thereafter. During the reign of Trajan, circa 103-107 CE, Pannonia was divided into Pannonia Superior and Pannonia Inferior, with Carnuntum being made the capital and seat of the governor for Pannonia. In the first few years of Hadrian’s reign (117-118 CE), Legio XIV Gemina was moved to Carnuntum, which would serve as the permanent headquarters of the legion until the 5th century CE. Superior. While visiting the Danubian provinces in 124 CE, Hadrian stopped at Carnuntum and the civic settlement was granted municipium as Aelium Carnuntum.

Early in the reign of Marcus Aurelius, pressure began to mount on the Danubian frontier from Germanic tribes, leading to the series of conflicts known as the Marcomannic Wars. Attempting to drive back Germanic raids, Marcus Aurelius led an imperial army to Carnuntum. While the presence of a large force here initially stemmed incursions, they quickly started back up again after the force was withdrawn. In the spring of 170 CE, a major battle was fought near Carnuntum between a force led by Marcus Aurelius and a combined force of Marcommani and Quadi under the command of Ballomar. The relatively inexperienced Romans were badly defeated by the Germanic force, losing about 20,000 troops and allowing the Germanic groups to break out in Roman territory, besieging and ravaging settlements as far afield as Eleusis and Aquileia. Carnuntum would be Marcus Aurelius’ base of operations while trying to regain control over the area between 172 and 174 CE. He would even write the second book of his Meditations while in the city.

In 191 CE, Septimius Severus was appointed governor of Pannonia Superior by Commodus, and resided at Carnuntum. Following the assassination of Commodus successor Pertinax in 193 CE, Legio XIV Gemina proclaimed Septimius Severus emperor at Carnuntum on the ides of August, and the subsequent support of surrounding legions allowed him to ascend to power. Shortly thereafter, in 194 CE, Septimius Severus would bestow the title Colonia Septimia Carnuntum upon the city. In the midst of the Crisis of the Third Century, in 260 CE, the usurper Regalianus, supported by the Danubian legions, would use Carnuntum as his seat of power. He may have been the governor of Pannonia Superior at the time. Regalianus seems to have been killed during a Roxolani raid on or around Carnuntum in 261 CE, but it has also been suggested that his own troops may have been responsible.

Following the turmoil created with the retirement of Diocletian and Maximian in 305 CE, a conference was held at Carnuntum in 308 CE to attempt to solve the breakdown of the tetrarchy, with Diocletian, Maximian, and Galerius in attendance. An earthquake severely damaged the city in the mid-4th century CE, and a short time later, in 374 CE, Carnuntum was destroyed in a Germanic invasion. The city was partially restored when Valentinian I used the military camp there as a base to fight back Germanic raids, but Carnuntum entered a period of sharp decline and was largely abandoned following the capture of Pannonia by the Huns in 433 CE.

Getting There: the remains and museum of Carnuntum are actually spread between two towns; Petronell-Carnuntum and Bad Deutsch-Altenburg. Both towns have train stations, and regional trains depart more or less hourly from Vienna during the day. The journeys from the main train station in Vienna typically require a change at one of the other local stations (usually Rennweg or the airport). It takes about an hour to get to Petronell-Carnuntum, slightly more to Bad Deutsch-Altenburg, and currently costs 9.60 Euro and 11 Euro respectively. The regional train runs between the two towns on an hourly basis. Both train stations require a little bit of a walk to get to the relevant sites. For me, it was easier to just walk between the two towns, than to walk to the first train station, get on the train, then walk from the second train station to the other site. There are also a few things worth seeing along the way between the two towns. A personal vehicle obviously eliminates that need. But, while parking is pretty plentiful for visiting the sites in Petronell-Carnuntum, it is less so in Bad Deutsch-Altenburg. Though the museum is outside the town center, so the parking isn’t unreasonable.

My most recent visit in August of 2021 was actually my second time seeing Carnuntum, my first being nearly 10 years previous in August of 2012. Both were done as day trips from Vienna. Most of the archaeological remains are in Petronell-Carnuntum, the site of the civilian settlement. Some scant remains of the legionary camp are located just outside of Bad Deutsch-Altenburg, and the site museum for Carnuntum is located within the town of Bad Deutsch-Altenburg. Again, I found the most productive and efficient way to visit was to take the train to Petronell-Carnuntum, see the remains in the area of Petronell-Carnuntum, then to walk toward Bad Deutsch-Altenburg, catching the things along the way. And finally to visit the museum and then take the train out from Bad Deutsch-Altenburg. The only issue with that being that the road between the towns is not particularly pedestrian friendly; but it’s also not an especially heavily trafficked road.

There are a few things that are a bit outside of Petronell-Carnuntum and require a little bit of a walk (or a drive) from the main site. If walking from the train station, the first is easiest to get to from there, rather than backtracking from the main site. This monument is the so-called Heidentor, or Heathen’s/Pagan’s Gate. This name supposedly came from the later folklore that the structure was the remains of a pagan giant’s tomb. In actuality, it seems to have been a tetrapylon triumphal monument erected by Constantinus II sometime during his reign, likely to commemorate a victory in the area; perhaps during his campaigns in Pannonia from 357 to 359 CE. No specific battle or dedication has been determined, though.

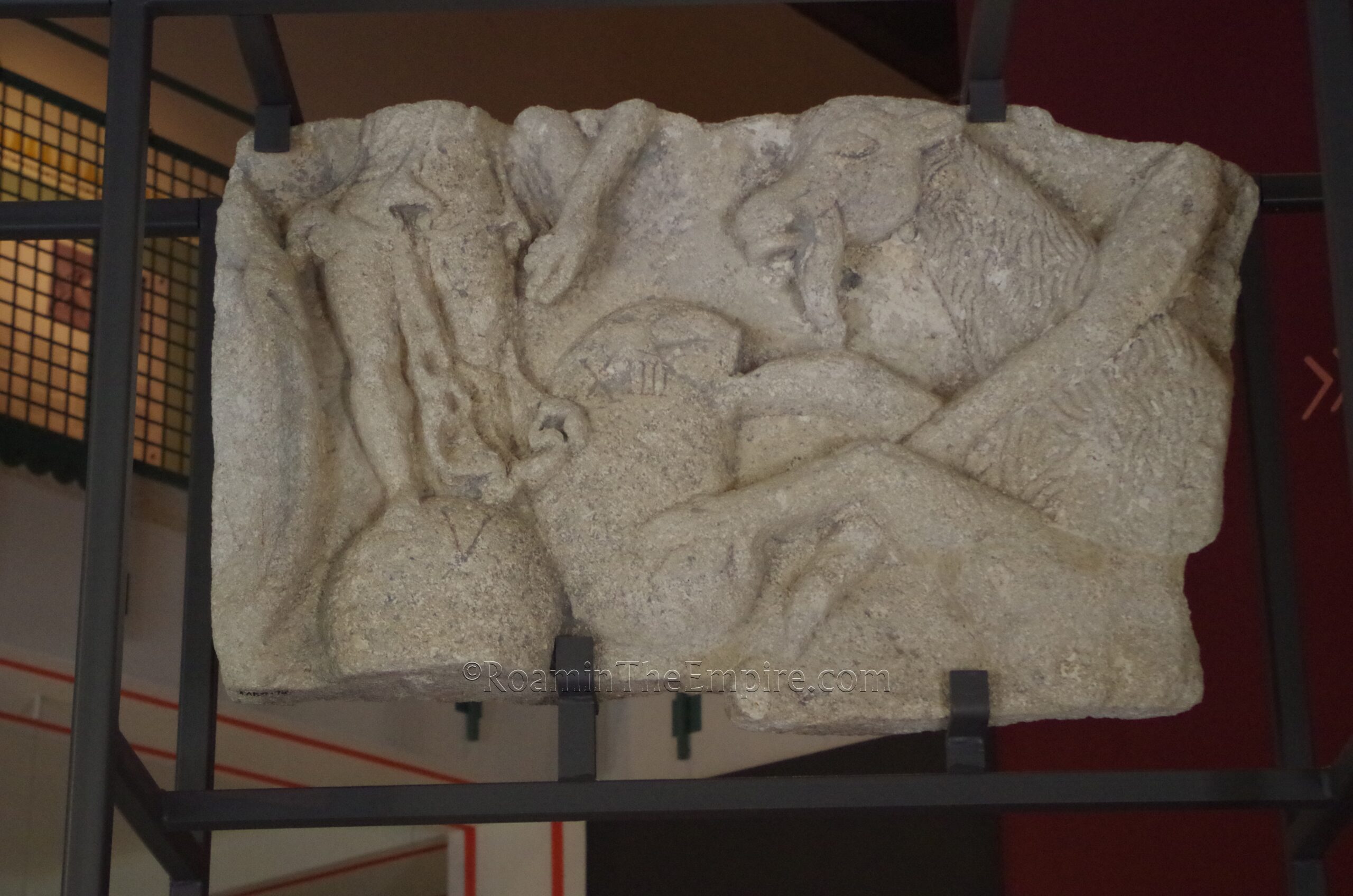

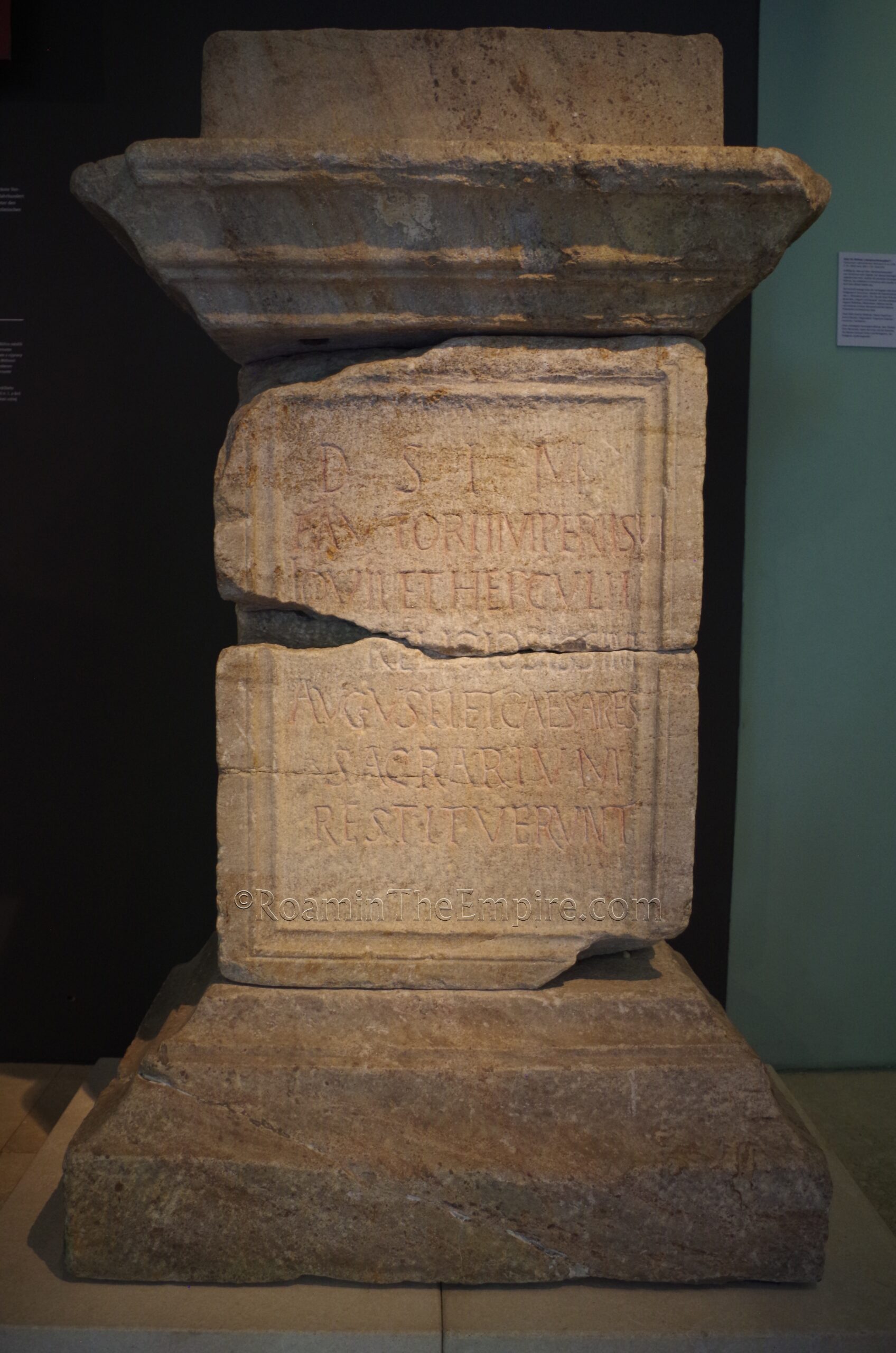

The monument was a quadrafrons arch, similar to the Arch of Marlborghetto, which Constantinus II’s father, Constantine, erected near Rome. Only one of these faces and arches survives, though the bases for the others are present (but not all are visible). The arch was constructed with the use of spolia; inscribed altars were found making up the interior core of the arch during restorations. The arch would have been decorated with sculptures, only fragments of which have been found. A large pedestal at the center of the monument likely supported a statue of Constantinus II, but perhaps also a deity. There are a few informational signs in English and German present, as well as some helpful diagrams and illustrations that reconstruct the arch.

About 650 meters north of the Heidentor is the amphitheater of the civilian settlement. The amphitheater is open access without any kind of restrictions. An inscription notes that the amphitheater was constructed in the latter half of the 2nd century CE by one Gaius Domitius Zmaragdus. Measuring about 130 meters by 110 meters, with an arena size of about 68 meters by 50 meters, the capacity of the amphitheater is estimated to have been 13,000 to 15,000 spectators. An inscription found here claims that it was the fourth largest amphitheater in the empire. In the 4th century CE, the amphitheater fell out of use and an early Christian church was constructed among the southern entrance of the building.

A fair amount of the foundations of the amphitheater survive. Though the seating is largely gone, the supports for the seating can be seen. The shape of the arena surface is slightly haphazard and is not a perfect oval. Recently a ludus has been identified to the west of the amphitheater. There is presently a small wooden amphitheater (of modern construction) on the spot of the gladiator school. Some initial excavations have been done, but nothing remains uncovered. Some hints of the underlying structures may be visible in the vegetation growing in the area, but it may also be the result of disturbances from these past excavations. One sign with some brief information in English, German, and (what I presume is) Slovak is present.

Continued In Carnuntum, Pannonia Superior – Part II

Sources:

Ammianus Marcelinus. Rerum Gestarum, 30.5.

Eutropius. Breviarium Historiae Romanae, 8.13.

Grant, Michael. A Guide to the Ancient World: A Dictionary of Classical Place Names. New York: Barnes & Noble Books, 1997.

Jerome of Stridon. Chronicon, A178, A308.

Pliny the Elder. Historia Naturalis, 4.25.1, 37.11.

Sedlmayer, Helga. Large City Baths of Colonia Carnuntum (Pannonia Superior/Austria): History Deduced From Waste. Archeologia Mosellana, Vol. 10, 2018.

Smith, William. Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography. Walton & Murray, 1870.

Stillwell, Richard, William L. MacDonald, and Marian Holland. McAllister. The Princeton Encyclopedia of Classical Sites. Princeton, NJ: Princeton U Press, 1976.

Unknown. Historia Augusta, Severus 5.

Velleius Paterculus. Historiae Romanae, 2.109.1.