Most Recent Visit: July 2022

Located today among the modern city of Astorga, in the province of León in northeastern Spain, was once the Roman settlement of Asturica Augusta. The area of the settlement was inhabited by the Amaci, a Celtic population that was incorporated into the tribal confederation of the Astures at some point prior to Roman contact. The name of the Astures was given due to their cultural group being centered around the Astura (modern Rio Esla) river valley. The Amaci were specifically part of what would be referred to by the Romans as the Astures Cismontini (or later the Astures Augustani), those residing on the nearer (southern) side of the Iuga Asturum (the modern Cordillera Cantábrica) mountain range. Though no archaeological evidence has been found to suggest habitation of the Amaci on the actual site of Asturica Augusta, there was certainly habitation elsewhere in the immediate vicinity.

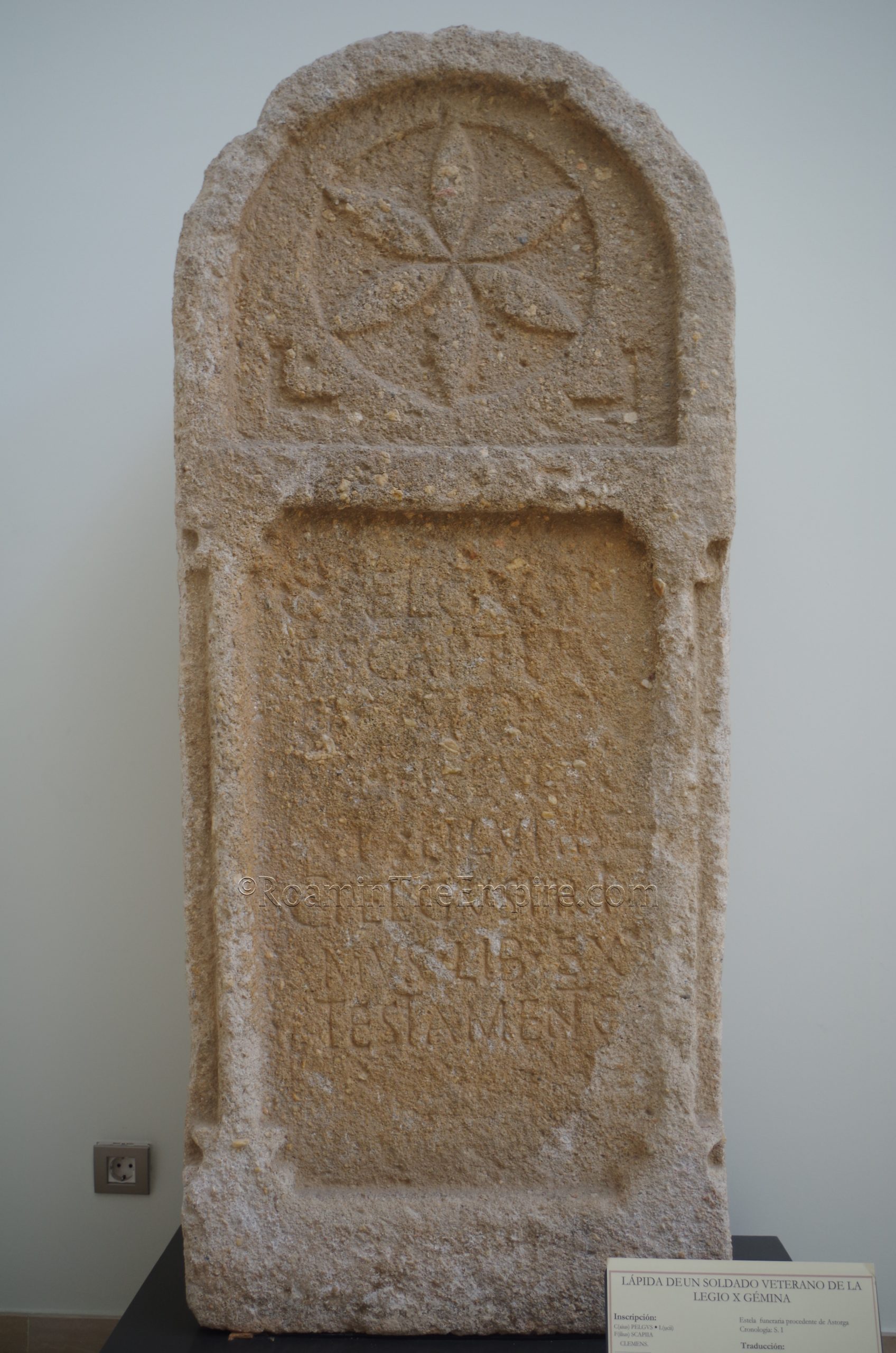

The Astures are noted as having provided mercenaries in the armies of Hasdrubal Barca and Hannibal during the Second Punic War. After that, though, they don’t seem to be involved in the early actions of the Romans to subdue the Cantabrian region of Hispania. By 29 BCE, however, the area of the Cantabrians and Astures remained the last subdued region in Hispania, and a series of campaigns were waged between 29 BCE and 19 BCE as the Cantabrian Wars to bring it under Roman hegemony. The main campaign against the Astures Cismontini occurred in 26-25 BCE as the Bellum Asturicum, at which time a Roman camp for Legio X Gemina was likely established at or near the site of what would become Asturica Augusta. The Astures Cismontini largely surrendered following their defeat in 25 BCE, but it wouldn’t be until 19 BCE that resistance in the mountains had largely been subdued.

Asturica Augusta was founded in 14 BCE as part of the Augustan organization of Hispania following the Cantabrian Wars. The name reflects the Augustan foundation and the territory of the people in which it was established. It served as the chief city for the Astures and was the capital of the administrative unit of the Conventus Iuridicus Asturum created toward the end of Augustus’ reign. The location served to help protect roads in the region and in particular, the route from the gold mines of the nearby Mons Medullius (modern Las Médulas) to the west and the roads from the silver mines to the south in the area of Augusta Emerita. Chrysocolla and minium were also mined in the area and . Pliny the Elder, who was procurator of Hispania Tarraconensis in 73/74 CE, wrote that Asturica Augusta was a magnificent city. Around the same time in 74 CE, the city along with all others in Hispania received Ius Latii under Vespasian, and was enrolled in the Quirine tribe.

Asturica Augusta seems to have been given municipium at some point, though the exact timing is unclear. From the time of the Flavians (and Pliny’s procuratorship) through the 2nd and 3rd centuries CE, the settlement seems to have flourished as gold mining . It was known particularly for its horse breeding. When gold mining in the region was drawn down in the late 3rd century CE, Asturica Augusta too experienced a decline in prosperity. During the reign of Caracalla, the city was apparently made capital of the new province of Hispania Nova Citerior Antonia. Under Diocletian, Austurica Augusta was reorganized into the province of Hispania Gallaecia. Around 409 CE, the Germanic Suebi people migrated into the area and established the Kingdom of the Suebi, including Asturica Augusta, and removing the city from the Roman hegemony. Conflicts with the Visigoths who later arrived in the region resulted in the sack of Asturica Augusta by Theodoric II in the middle of the 5th century CE. It was later incorporated into the Visigothic Kingdom in the late 6th century CE.

Getting There: Astorga is not a particularly large city, but it does have a railway station that connects it with other larger cities. For instance, there are a few departures daily that will get one from Madrid to Astorga. None of the trains are direct, but it takes between 2:50 and 4:15 to get from Madrid to Astorga with tickets starting at 53 Euros and going up to about 70 Euros depending on departure time and train service. From the other major city in the region, Zaragoza, the journey is cheaper but twice as long and with less frequent departures. Schedules can be checked here. I arrived in Astorga with a private vehicle, and there is free parking available east of the Parque del Melgar in the lower town, or in the adjacent streets if the parking lot is closed, as it was when I visited. From there the city is very walkable and the main sites are not far. If arriving by rail, the station is a bit farther outside of town, but still less than a 10 minute walk beyond the parking area.

The Roman era remains of Asturica Augusta in Astorga can be divided into two categories; the sites which can be visited independently, and those which can only be seen as part of a guided tour that can be booked through the Museo Romano La Ergastula. It’s also worth noting that the area was experiencing heavy wildfire activity when I visited, so some of the pictures I use for this stop have a heavy yellow tint to them from the smoke that was enveloping the city during one of the two days I visited Astorga.

Starting with the open access sites, the first thing most would encounter upon arriving at the city would be the remains of the city walls running along the south side of the Parque del Melgar. The Roman circuit of walls was constructed in the late 3rd or early 4th century CE in response to the increasing pressure of Germanic invasions/migrations of Roman territory in the western part of the empire. Much of what is visible today, however, does not date to the Roman period. The walls were reconstructed in the 13th century CE, and repaired variously through the medieval period. The thirteen rounded towers visible on this stretch of walls also date to the 13th century reconstruction. There is a distinct difference in the construction of the lower half a meter or so of the wall in some places, which may indicate the division of the periods of construction.

At the west end of this part of the walls is an excavated area in which the remains of a gate dating to the 3rd/4th century circuit of walls can be seen. This was apparently the principal entry into the eastern side of the fortified city. The gate is pretty fragmentary, but the form of it can be seen, including one of the circular towers that flanked the entrance, which is partially reconstructed with modern materials. Both the walls and the gate remains are in public areas with open access, so they can be visited at any time. There is a small informational sign in Spanish located here.

About a 5 minute walk to the southeast of the Roman gate, toward the center of what would have been the center of Asturica Augusta, are some remains that are commonly identified as belonging to a bathing complex, but are referred to in most information as just uncovered constructions, with no specific attribution. These are located on the south side of Calle Santiago Crespo, just south of the intersection with Calle Postas. Unfortunately, though they are clearly there and mostly uncovered according to satellite imagery, they are not visible from ground level. There is a tall, opaque metal fence that has no gaps or any other sort of way to see beyond it, so the excavated here is completely hidden from the street.

Another 500 meters or so of walking south, through a slight maze of streets, just to the south of Plaza España, one of the main plazas in this part of town, are part of the excavated remains of the forum of Asturica Augusta. The forum of the settlement was constructed in the 1st century CE, with an orientation somewhat askew of the previously constructed areas of the city to the northwest. This was also the highest point of the already elevated area on which the city was constructed. The area excavated here is quite large, measuring over 50 meters at its widest and about 33 meters in length, though the shape is irregular. In the northern part of this excavated area are the remains of the portico that bounded the southern side of the forum. The column bases are clearly visible, and one of the apsidal niches along the exterior wall of the portico is also visible. There are some additional unspecified remains to the south of that. Like the gate in the fortifications, there is a small informational sign with a very basic description in Spanish.

From the southern point of the excavated area of the southern portico of the forum, diagonally across the street to the south is the Jardín de La Sinagoga. This public park overlooks the southern edge of the elevated town center. This part of the upper town also preserves part of the later wall and a six of the towers. It’s not really visible from the street below, so the perspective from atop one of the towers (which is ground level with the park) is probably the best way to see this part of the wall. Again, what is visible is pretty much exclusively the later 13th century CE reconstructions, but it follows the course of the original Roman fortifications. The park is public, but gated and presumably closes, though no hours are posted. It should seemingly be open during daylight hours and likely into the early evening at least.

Continued in Asturica Augusta, Hispania Tarraconensis – Part II

Sources:

Grant, Michael. A Guide to the Ancient World: A Dictionary of Classical Place Names. New York: Barnes & Noble Books, 1997.

Marcos, Victorino García and Julio M. Vidal Encinas. “Recent Archaeological Research at Asturica Augusta.” Social Complexity and the Development of Towns in Iberia, From the Copper Age to the Second Century AD, Barry Cunliffe & Simon Keay, Proceedings of the British Academy Vol. 86, 1995, pp. 371-394.

Pliny the Elder. Historia Naturalis, 3.4.9.

Ptolemy. Geographia, 2.6.30.

Smith, William. Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography. Walton & Murray, 1870.

Stillwell, Richard, William L. MacDonald, and Marian Holland. McAllister. The Princeton Encyclopedia of Classical Sites. Princeton, NJ: Princeton U Press, 1976.