Most Recent Visit: June 2022

The Roman settlement of Aventicum, located on the shores of the modern Murtensee, not far from the Eburodunensis Lacus (modern Lake Neuchâtel), has an uncertain foundation date. Today located among modern Avenches, Switzerland, in antiquity Aventicum was located in the territory of the Helvetii, specifically that of the Tigurini branch. There does not seem to be a pre-Roman settlement at the site of Aventicum, though a few have been identified in the immediate vicinity. Following the attempted migration of the Helvetii in 58 BCE and subsequent intervention by Julius Caesar, the Helvetii became foederati of Rome, but again came into conflict with Rome in 52 BCE when they supported the uprising of Vercingetorix, likely losing this status. It was in that last half of the 1st century BCE, that two oppida in the vicinity of Aventicum seem to have been established, as the Helvetii, now under Roman hegemony, increasingly adopted Roman culture.

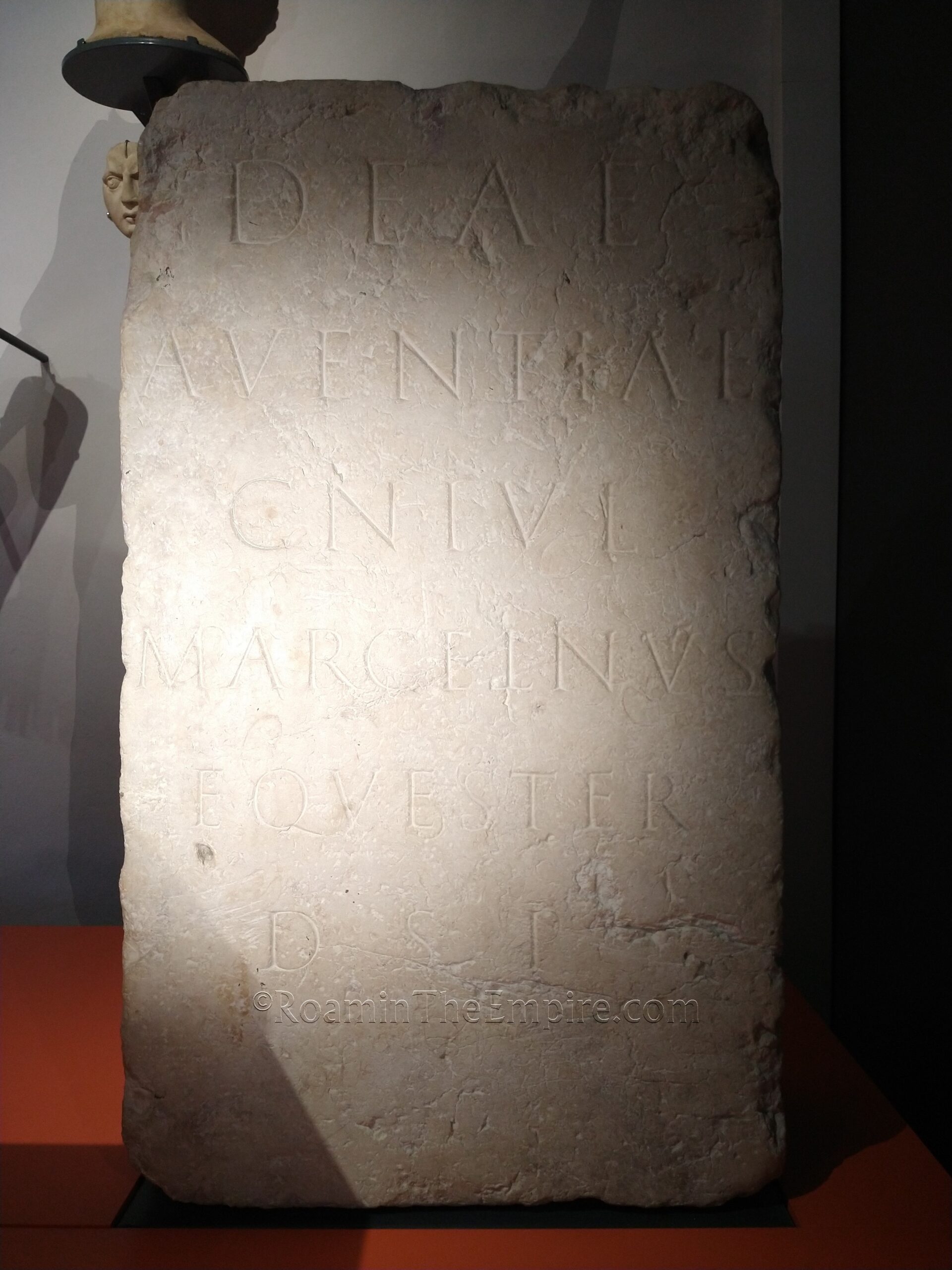

It seems as though it was in the waning years of the 1st century BCE or the early years of the 1st century CE, that Aventicum was founded. The city was likely established to serve as the administrative center of the Helvetii, described by Tacitus in the 1st century CE as a caput gentis. This was probably due to a prominent placement on important roads and trade routes through the region. Under Augustus, it was incorporated into the province of Gallia Belgica. The name of the city seems to derive from the Gallic patron goddess of the area, Aventia. In the strife that followed the assassination of Nero, the cities of the Helvetii supported Galba in his bid for the throne. Forces loyal to Vitellius besieged many of these cities, but Aventicum surrendered as soon as the troops of Vitellius moved on the city. Aventicum was only spared destruction through the efforts of one Claudius Cossus, who convinced Vitellius to spare the Helvetii settlements.

Around 73-74 CE Vespasian founded a colony of veterans at Aventicum, giving it the title Pia Flavia Constans Emerita Helvetiorum Foederata. Vespasian’s father, Titus Flavius Sabinus was a banker in Aventicum (possibly at the suggestion of Vespasian himself) and had died there in 69 CE. Epigraphic evidence would seem to indicate Vespasian’s son, Titus, spent some of his youth in the city as well. The establishment of the colony of veterans was meant to increase the security of the trade routes running through the region, including the road between Augusta Rauricorum (modern Augst) and Lousanna (modern Lausanne). It was after this period that many of the large building projects occurred. Aventicum prospered through the 2nd and 3rd centuries CE, estimated to have had a population of about 20,000 inhabitants in the 2nd century CE. It seems to have been heavily damaged in the Alemanni incursions circa 275 CE. Though it was not completely abandoned after the destruction, the city was never quite able to recover and large parts of the city fell into disuse and Aventicum entered a period of decline that persisted through to the end of the Roman period. It was the seat of a bishopric in the 5th century CE.

Getting There: The closest major city to Avenches is Bern, about half an hour to 45 minutes by car, but also reachable by train. Trains routes from Bern to Avenches are available a couple times an hour for most of the day. Unfortunately, though, there are no direct trains, all routes between the two require at least one change. As such, the trip can take anywhere from 45 minute to an hour and a half, and cost between 8 and 15 CHF each way. The return trip frequency is about the same. Frequency from Lausanne is about the same, but the trip is generally longer and more expensive. Most of the sites in the town are pretty walkable, though the eastern walls and gate are a bit far without a personal vehicle.

If you come by train (or even by car) one of the most logical places to start is a stretch of the northern fortification walls near the train station. The city walls of Aventicum were constructed around the same time that it was given colonia status by Vespasian. The circuit of the walls was about 5.5 kilometers in total, enclosing a space of about 230 hectares. The northern walls of the city are visible along the appropriately named Chemin Derrière les Murs, literally behind the walls. This road is paved just to the northwest of the train station, but then turns more or less into a dirt road until it intersects with Route de l’Estivage. Along Chemin Derrière les Murs. Significant portions of the walls are visible along the dirt road and the last little bit of paved road.

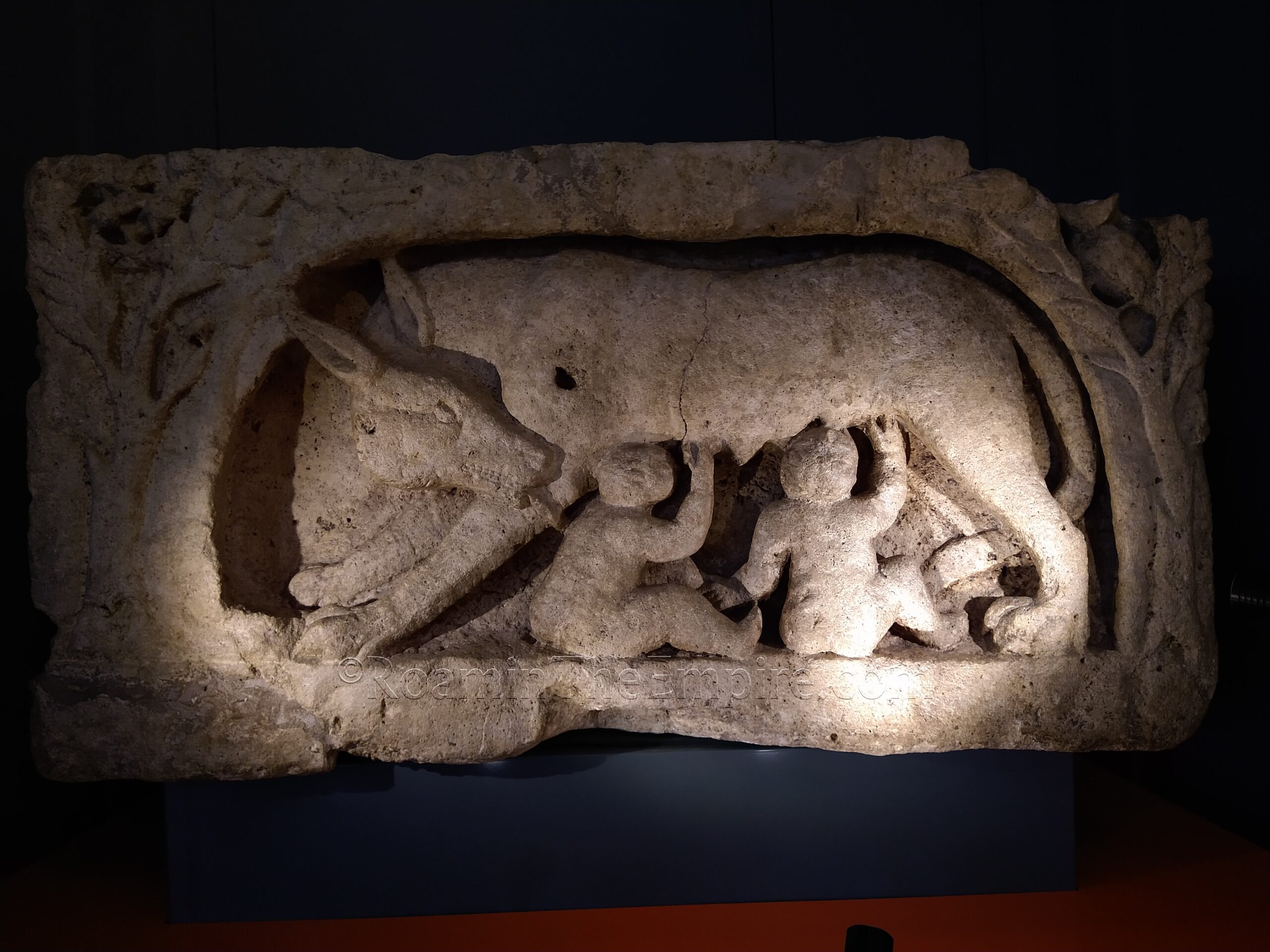

From the train station it’s a short walk (400 meters) southeast to the so-called Palais de Derrière la Tour, located at Rue du Pavé 6. Located down a slope on the north side of the street, abutting the residential building, are the remains of a rounded wall and intersecting wall from the Roman period. As the name would suggest, this seems to be associated with a palace of sorts, or more accurately a very wealthy residential building. Initially constructed in the middle of the 1st century CE, it was then expanded in the 2nd century CE. The extent of the structure is apparently well known from excavations, but only this small bit of a basin belonging to the bathing rooms remains visible. A relief of the she-wolf suckling Romulus and Remus, one of the centerpieces of the museum, was found in this residence. Inscriptions found here also indicate that it may have been associated with the Otacilii family, one of the preeminent families in Aventicum.

From there, it’s another short walk to the center of the old town (though a bit uphill) and the vicinity of some of the main monuments, such as the amphitheater. Before getting to those, though, it is worth a small diversion southwest down Rue Centrale, the main road of the old town which terminates (or begins) at the amphitheater. About 350 meters down Rue Centrale is the Église Sainte-Marie-Madeleine d’Avenches, at the intersection of Rue du Temple. On that corner of the building, built into the corner of the building, is a rather large piece of entablature identified as likely having come from the so-called Sanctuaire du Cigognier. At the opposite end of the building, at the intersection with Rue de la Cure, is another similar piece of entablature. The original 11th century CE church that stood here was reportedly constructed with stones spoliated from the Roman fortification walls.

About 775 meters on, after Rue Centrale actually terminates and turns into Route de Lausaunne, at the northeast corner of the intersection with Route de la Province, is a small park containing a water feature that has a modern column topped with an ancient capital. The context of the capital doesn’t seem to be known, though.

From there, however, it’s a short walk down Route de la Province to the roundabout and then east less than 50 meters down Route du Faubourg to the remains of the western gate in the city walls of Aventicum. On the south side of the street, the foundations of the southern tower of the west gate is preserved a little bit below the road level. An informational sign nearby illustrates and diagrams the form of the gate and gives a short explanation of the gate and the city walls in general in French, German, and English. Like the rest of the walls, the gate seems to have been constructed after the establishment of Vespasian’s colony here.

Tracking back to the central part of the old town is the amphitheater. It is essentially a public park and is more or less open access. The amphitheater seems to have first been constructed about 130 CE. It was built by carving out a space in the natural slope of the hill with the hill providing support for most of the lower part of the cavea. The seating, and the seating support that extended above the slope of the hill was likely constructed predominately with wood. The seating had 24 rows and a capacity of about 9,000 spectators. A semicircular forecourt was built at the east entrance. A few decades later, around 165 CE, the amphitheater was significantly expanded. The dimensions of the amphitheater grew from 99 by 86 meters to about 105 by 92 meters. The seating and the structure of the amphitheater above the natural terrain was not constructed in stone and an additional 7 rows of seating was added to bring it to 31 rows. The capacity grew to about 16,000 spectators with this expansion. The amphitheater stopped being used as an entertainment venue in the 4th century CE and was spoliated of building material for use in other buildings from that point on.

The amphitheater as it stands today is heavily reconstructed. Particularly the north side of the seating, which is mostly modern. The south side with some very limited remains of the seating better reflects the natural state of the theater. Though that may have changed (permanently or temporarily) recently as the south side appears to have some kind of structured seating now. Only 20 rows of seating survive/are reconstructed, as the superstructure above the natural terrain is more or less gone. The retaining wall along the south side is also modern. The monumental entrance on the east side (constructed as part of the 165 CE expansion), leading in from the remains of the forecourt, allows access to the arena. Inside the entrance (though it can also be accessed from the seating at this end). Inside this entrance, along the north side of the amphitheater, some remains of the wall from the original construction phase can be seen (explained by a nearby sign). Some remaining exterior blocks delineate an internal tunnel that ran along the south side of the arena. A sign with general information on the amphitheater is located in the forecourt.

Continued In Aventicum, Gallia Belgica – Part II

Sources:

Grant, Michael. A Guide to the Ancient World: A Dictionary of Classical Place Names. New York: Barnes & Noble Books, 1997.

Levick, Barbara. Vespasian. New York: Routledge, 1999.

Smith, William. Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography. Walton & Murray, 1870.

Stillwell, Richard, William L. MacDonald, and Marian Holland. McAllister. The Princeton Encyclopedia of Classical Sites. Princeton, NJ: Princeton U Press, 1976.

Suetonius. De Vita Caesarum Vespasian, 1.

Tacitus. Historiae, 1.67-70.