Continued From Apollonia, Macedonia – Part I

From the tower, the road begins to slope uphill toward the main archaeological site. Another 250 meters on or so, on the east side of the road, are the remains of a large residential building. The residence, referred to as the House of Athena after a statue of the goddess found there (also sometimes called D House), is on a rise above the road and is best visible from the south end of the structure. Unfortunately it is fenced, so there is no direct access. One of the outer walls of the house seems to date back to the 3rd to 2nd century BCE, but the main structure and form the building reflected today seems to date to the 2nd to 3rd century CE, with some renovations in the 4th century CE. A number of mosaics were found in the building, but are presently covered for preservation reasons (and would be inaccessible and largely not visible because of the restricted access of the fence).

Continuing up the modern street a few meters, there are some more constructions of an unidentified building on the east side of the road. A few more meters beyond that, the modern street crosses the so-called Street H, a roughly 125 meter stretch of a decumanus. A little more than 80 meters of the street is uncovered on the west side of the modern road, and another 40 or so meters on the east side. In addition to being the larger portion of the street, the west side is significantly better excavated and preserved. The west side is excavated down to the paving stones of the road in some places, revealing an interesting paved channel along the south side of the road. The remains of some of the structures immediately adjacent to the road have also been excavated and are visible. This part of the road is relatively level, while the portion on the east side of the modern road begins sloping up the hill. This part is mostly unexcavated with just some of the structures adjacent to the street visible, but clearly showing the path the road took up the hill. Both sections are fully accessible.

Walking up the eastern part of the Roman road, up the hill (but can also be reached in a roundabout way via the modern road from the site parking lot) leads to a path that doubles back to the theater. The theater was originally constructed in the 3rd century BCE, employing the slope of the hill as support for the seating of the monument. Like other theaters in the region, it was altered a few times during the Roman imperial period in order to allow for arena spectacles to be featured. At one point, the scena was removed in order to increase the size of the orchestra, which now served as the arena floor. Another building was constructed in the area of the scena in the final phase of construction. The capacity is estimated to have been about 7,000 spectators.

The theater seems to have been destroyed in the 3rd century CE. At some point in late antiquity or post-antiquity, a church was built on the site. Both this church and the nearby Monastery of Saint Mary (which houses the archaeological collection) were constructed using the building materials from the theater. As such, there isn’t a whole lot of the building material of the theater left in situ. All the seating appears to be gone, or is not exposed, except for the very edges along the orchestra. Some construction in the orchestra and stage area is visible. A lot of loose stonework is piled behind the scena area, presumably at least some of it recovered from the church that once made use of it. The whole area is open and accessible. There’s a path that leads up the seating to the top. The theater is also outside of the archaeological park and accessible at any time.

Retracing back to the main road, it’s just 130 meters up to the parking lot for the archaeological site. Among a stand of trees in the northern part of the parking lot, are some scattered walls constructed of large stone blocks. These belong to a residential building, the so-called Léon Rey houses; named after the French archaeologist who excavated at Apollonia. Directly across the modern road to the east are some more remains with the large blocks and bricks. These are from a residential building as well, the so-called house of Sector F. Both of these are open access and still outside the actual archaeological area.

The Archaeological Park of Apollonia (Parku Arkeologjik i Apolonisë), which also includes an on-site museum, is open every day in the summer (May through October) between 9:00 and 19:00. The rest of the year it is open Tuesday through Sunday from 9:00 to 17:00 and is closed on Mondays. Admission to the archaeological area is 600 Lek.

Immediately inside the archaeological park is the Monastery of Saint Mary. Some of the buildings of the 13th century monastery house the archaeological collection of Apollonia. There is no separate entrance required, as it is inside the archaeological area, but it does close an hour before the rest of the archaeological park. It is believed that the site of the monastery (and previously a Christian basilica in the 4th century CE) was once the site of a temple, possibly one dedicated to Apollo, though little is actually known about any potential temple at this location. The monastery was constructed using building material spoliated from the theater and other ancient buildings of Apollonia, though I didn’t notice any particularly distinctive pieces (ancient inscriptions or reliefs) used in the church or surrounding monastery.

The refectory, located just south of the entry in the southwest part of the complex has some excavations in the floor which reveal a section of mosaics which decorated the 4th century CE Christian basilica. Along the southeast side of the complex is a modern portico which houses the lapidary collection. There were a number of inscriptions (many funerary in nature) and statues as well as some architectural elements and a few mosaics. It’s not terribly large, it only took me about 15-20 minutes to go through it. At the northeast corner of the complex is an excavated area that doesn’t really have much information. It certainly predates the 13th century monastery, and this effectively abuts the eastern fortification walls, upon which the eastern side of the monastery is constructed. Some of the excavations here could be associated with the walls, but the columns and paving stones revealed don’t seem to be directly associated with the fortifications, as there was no gate at this location.

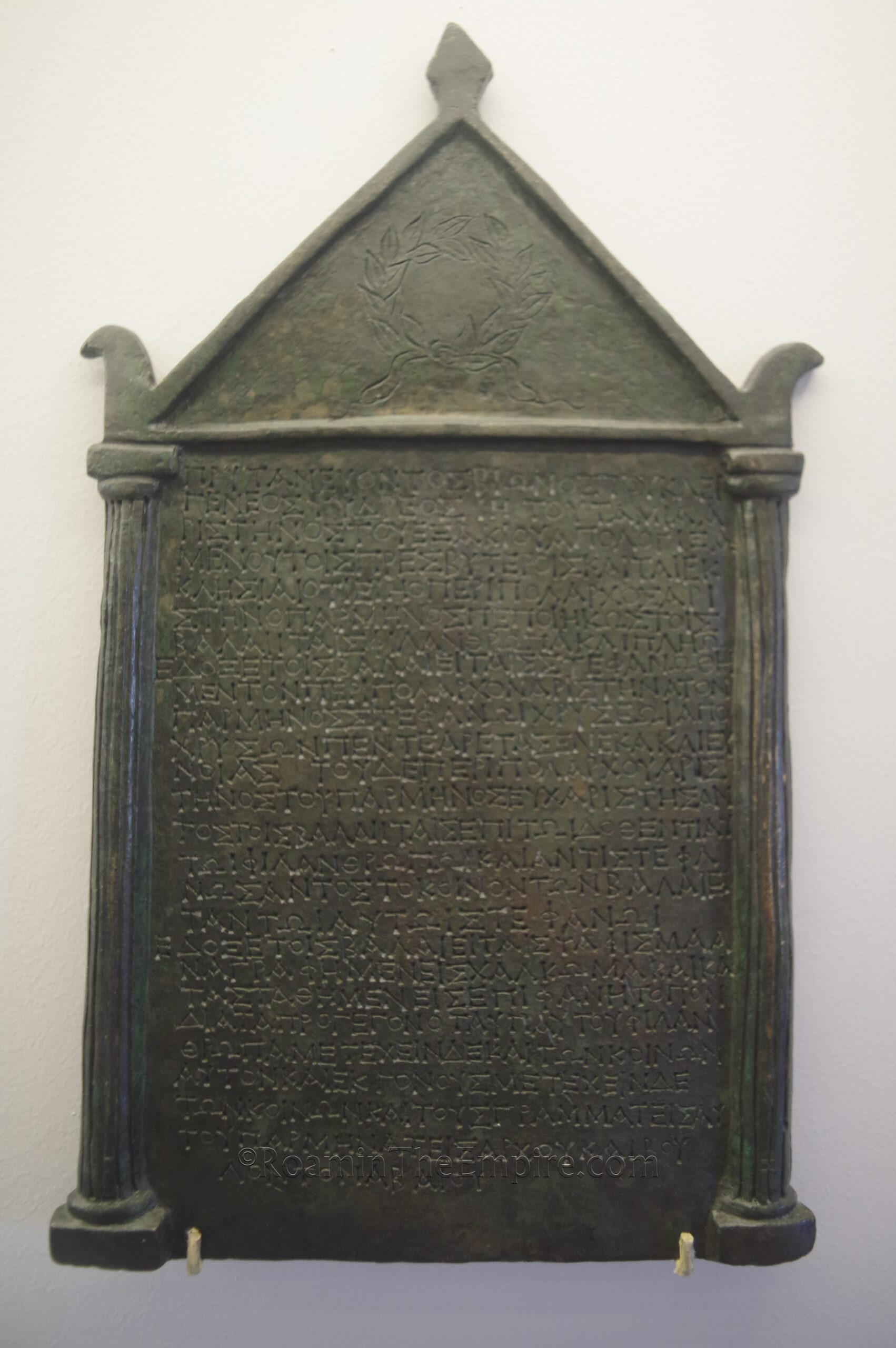

The main part of the museum is located in the second level of the northwestern wing of the monastery. This part of the collection includes the small finds, bronze pieces, portraits, and some of the nicer statues and reliefs. There are some really nice reliefs and bronzes, but unfortunately the information is somewhat lacking. While descriptions are given in both English and Albanian, which is nice, the museum card often leaves out dating of any kind and almost never gives much context. Some objects have no information at all. What I thought was one of the nicer and more interesting pieces in the collection, an inscribed bronze tablet in Greek, had absolutely no information at all. I still can’t find any secondary information on it, so it makes it double unfortunate that the museum had no information. It had some material from the Greek period of the city, which was nice. It’s a reasonably sized museum, it took me about 45 minutes to go through it. A number of the more important finds from the site are housed in the National Archaeological Museum and National History Museum in Tirana.

Though the main site is to the north from the entrance and monastery, there are a few points of interest to the south that are worth visiting. About 80 meters southwest of the monastery entrance, about even with the southern building of the complex, is the so-called Villa with Impluvium. As the name would suggest, it is a large residential building with an impluvium. A modest house was originally built on this site in the 2nd century BCE, but it was significantly expanded in the early 1st century CE. It seems to have been mostly destroyed sometime in the late 2nd century CE, perhaps due to earthquake damage, but was rebuilt. The building was then abandoned in the 4th century CE. Mostly what remains are the northeast rooms that are built around a central courtyard with an octagonal impluvium, which is not visible. Mosaic flooring that surrounded the feature is also covered. There’s no direct access to the house, as it is fenced. There are some remains of an unidentified building about halfway between the monastery and house as well.

Another 80 meters south of this is another rectangular building, the so-called Sestieri building, named after another one of the excavation directors at the site. This was another presumably residential building. This area was somewhat overgrown. About 500 meters beyond this, past the cemetery and to the southwest, is the southern gate of the city. Because of the distance and the fact that the area looked significantly overgrown, I didn’t venture out that far feeling that it was a pretty low possibility that I’d actually be able to see anything there.

Continued in Apollonia, Macedonia – Part III

Sources:

Amore, Maria Grazia. The Complex of Tumuli 9, 10 and 11 in the Necropolis of Apollonia (Albania). Vol. 1. Oxford: BAR Publishing, 2016.

Appian. Bella Civilia, 2.8-2.10.

Appian. Bellis Illyricis, 2.8.

Appian. Syriaca, 4.17.

Aristotle. Politika, 1290b.

Bereti Vasil, Quantin François, Cabanes Pierre. Histoire et épigraphie dans la région de Vlora (Albanie). Revue des Études Anciennes, Volume 113 (2011), No. 1, pp. 7-46.

Cassius Dio. Historia, 10.42, 10.141, 12.19, 18, 19.19.1, 41.45-47, 45.3.1, 45.9.3, 47.21-24, 55.29.3.

Değerlendirme, Yeniden. “The Athena Domus at Apollonia (Albania): A Reassessment.” Uludag University Journal of Mosaic Research, Volume 9 (2016), pp. 23-28.

Diodorus Siculus. Bibliotheca Historica, 18.15, 18.58, 19.19, 19.67-70, 19.78, 19.89.

Grant, Michael. A Guide to the Ancient World: A Dictionary of Classical Place Names. New York: Barnes & Noble Books, 1997.

Julius Caesar. Commentarii de Bello Civili, 3.

Livy. Ab Urbe Condita, 24.40, 26.25, 29.12, 31.18-40, 35.24, 37-38, 40.58, 42.18-55, 43.21, 44.30, 45.28-44.

Nicolaus of Damascus. Bios Kaisaris, 16-18.

Omari, Elda and Paolo Bonini. “The Athena Domus at Apollonia (Albania): A Reassessment”. Journal of Mosaic Research, no. 9, 2016, pp. 23-38.

Pausanias. Hellados Periegesis, 5.22.3-4, 6.14.13.

Pliny the Elder. Historia Naturalis, 3.26.2, 24.25.1, 35.51.1.

Plutarch. Brutus, 22, 25-26.

Plutarch. Caesar, 37-38.

Plutarch. Sulla, 27.1.

Polybius. Historiae, 2.9.6, 2.11, 5.109-110.

Sear, Frank. Roman Theaters: An Architectural Study. Oxford: Oxford university Press, 2006.

Smith, William. Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography. Walton & Murray, 1870.

Stillwell, Richard, William L. MacDonald, and Marian Holland. McAllister. The Princeton Encyclopedia of Classical Sites. Princeton, NJ: Princeton U Press, 1976.

Suetonius. Augustus, 8, 95.

Thucydides. Historia, 1.26.

Vitruvius. De Architectura, 8.3.8, 10.16.9.

Wilkes, John. The Illyrians. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell, 1992.